(Phnom Penh): If Cambodia says “Thailand is invading,” Thailand replies, “Cambodia is provoking.” If Cambodia invokes international law, Thailand accuses Cambodia of “stirring up trouble.” And if Cambodia seeks historical evidence, Thailand increases pressure—warning Cambodia not to “make it bigger.” This is not ordinary diplomatic wordplay. It is a calculated strategy designed to control the narrative while simultaneously attempting to create a new “border line” on the ground.

As the Royal Government of Cambodia continues to assert that the Cambodia–Thailand border is an international border protected by international law, and that disputes must be resolved peacefully through mechanisms such as the JBC and legal avenues, the key question today is not how loudly Cambodia should speak. The real question is: What game is Thailand playing to force Cambodia to speak less—or to silence Cambodia entirely?

Thailand’s Strategy: “Applying Pressure” While “Spinning the Narrative”

Threats that “a third war could erupt,” or accusations that Cambodia is “disturbing” or “provoking” Thailand, do not necessarily signal a genuine intention to launch a full-scale war immediately. In modern strategy, such messages function as tools of pressure—combining rhetoric, information operations, and actions on the ground to gain leverage.

This approach typically serves three major objectives:

(A) Psychological Pressure

Threatening a “third war” is a psychological tactic intended to spread fear and despair. When society becomes anxious, it becomes easier to divide, easier to mislead with disinformation, and easier to pressure a targeted state into changing its stance simply to restore calm quickly.

(B) Narrative Spin

The use of disinformation—and allegations that Cambodia is the instigator—aims to shape international perception so the world concludes that “both sides are equally at fault.” Alongside this, some Thai official statements have called for an end to “false information and disruptive activities,” essentially placing blame on Cambodia and attempting to frame Cambodia’s position as contrary to “peaceful settlement efforts.”

The objective is clear: to damage credibility, blur accountability, and push public opinion toward a false equivalence—making it harder for international audiences to identify aggression and responsibility.

(C) Creating “Facts on the Ground”

The placement of containers, barbed wire, roadblocks, or construction in disputed areas—while Cambodia protests—should not be viewed as routine security measures. It is a strategy to turn physical control into bargaining power.

In border negotiations, if a situation on the ground is allowed to persist long enough, it can be used as a “de facto reality” to pressure the other side to negotiate from the current situation, rather than from the original legal baseline.

International law is clear in principle: a situation created under threat or force cannot produce legitimate legal rights. But in political practice, if such actions are not met with consistent opposition and formal protest, they may generate the misleading impression that the other side has “quietly accepted” the new reality.

That is why Cambodia has issued formal protests regarding containers and related actions that are viewed as undermining Cambodia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Such protests are not emotional gestures—they are legal safeguards designed to ensure that today’s temporary actions do not become tomorrow’s “accepted” status.

In short, the “facts on the ground” strategy relies on time. Without sustained legal and diplomatic responses, temporary control can become the new starting point for negotiations. With consistent documentation and formal protest, Cambodia preserves its legal position and demonstrates that it has never recognized border change by force.

Bilateral Mechanisms Are Lawful—But Bilateral Talks Under Force Are a Serious Problem

Thailand frequently argues that border disputes should be resolved through bilateral mechanisms, and that the International Court of Justice (ICJ) should not be pursued for new cases.

Under international law, bilateral negotiation is a legitimate method of dispute settlement. Article 33 of the UN Charter recognizes peaceful means such as negotiation, mediation, conciliation, and other methods.

But the problem is not “bilateralism” itself. The problem is the conditions under which bilateral talks occur.

If bilateral negotiations take place under circumstances involving:

- threats or use of force,

- creation of new realities on the ground, or

- coercion to keep one side silent or prevent it from describing the situation truthfully, then the negotiations risk undermining the core principle of free consent.

Under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, agreements concluded under coercion—especially through threat or use of force—may be regarded as lacking validity. In practical terms, if “facts on the ground” are created first and then used as the starting point for talks, negotiations can shift from a forum for restoring legality to a forum for indirectly legitimizing occupation.

International law maintains a clear principle: border changes achieved by force cannot create lawful rights. Therefore, if bilateral negotiations are used to pressure the other side into silence or passive acceptance, this is not sincere negotiation—it is the conversion of military pressure into political advantage.

Cambodia’s Long Path: Law + Evidence + Diplomacy

Cambodia has made clear that border disputes cannot be resolved on emotion or temporary conditions on the ground. Cambodia’s approach rests on international law, historical documentation, and technical evidence as the foundation of a durable settlement.

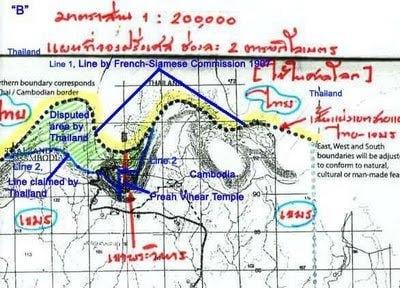

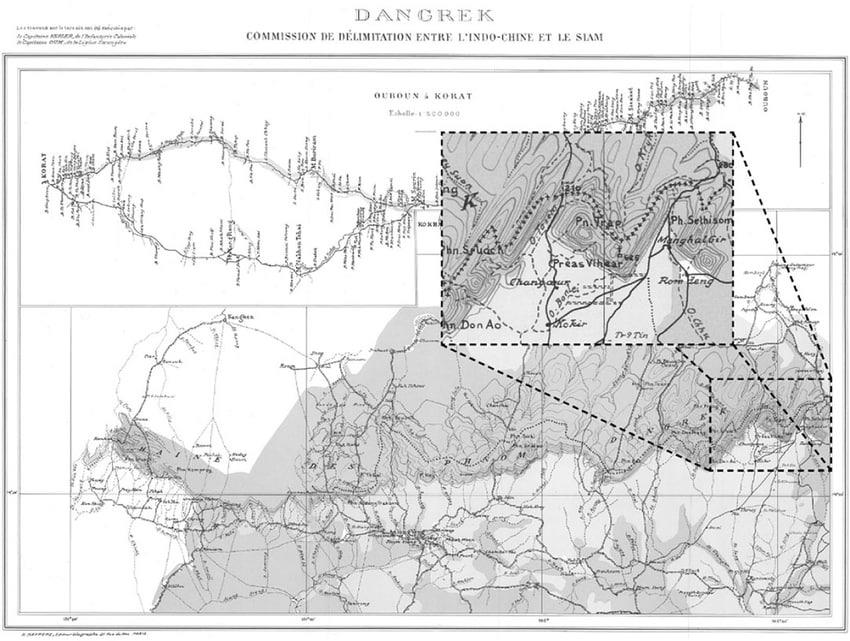

Cambodia’s reported request for relevant documents from France—given France’s historical role in border delimitation under the 1904 and 1907 frameworks—reflects an effort to strengthen an evidence-based case grounded in official records. This is not a short-term political maneuver. It is the building of a documented legal foundation that can stand in international forums and cannot be easily distorted.

This path may seem slow, but it increases the credibility of Cambodia’s position, strengthens prospects for international recognition, and reduces the space for manipulation or narrative reversal.

History also reinforces this logic. The Preah Vihear case demonstrated that international legal avenues may take time—1962 and further clarification in 2013—but they can produce internationally recognized outcomes with long-term stability.

At the same time, the humanitarian situation along the border—loss of life and displacement—has been repeatedly reported by international media, even amid repeated ceasefires. This underscores a vital truth: temporary quiet is not the same as lasting stability.

That is why “seeking justice” and “preventing war from returning” require a path that can stand for the long term—supported by law, evidence, and diplomacy—rather than short-term deals driven by immediate pressure.

What Should Cambodian Citizens Do in a Disinformation War?

This is the most important point. When pressure is applied, one key objective is to make Cambodia lose psychologically before losing any territory. Cambodian citizens can help protect national resilience by practicing at least six essential steps:

1. Do not share information without verified sources.

2. Do not allow instant anger to become a tool for others to spin the story.

3. Support legal and diplomatic strategy, understanding that a “long path” is not a “weak path.”

4. Support displaced people and victims through real solidarity—humanitarian aid and community care.

5. Criticism is legitimate—but it must be responsible, so it does not become a weapon that fractures national unity.

6. Keeping faith in the nation means thinking deeply and standing on national principles. In an information war, the enemy does not always need bullets to divide society. It only needs the collapse of confidence and psychological fragmentation. National faith therefore means preserving rational judgment—so fear or anger does not destroy our capacity to evaluate reality.

Conclusion

Threats and disinformation are not merely designed to provoke fear. They are attempts to silence Cambodia and to transform temporary “facts on the ground” into a new reality. But temporary reality cannot replace legal reality. Force can create pressure, but it cannot create lawful rights.

Cambodia should never be forced to choose between “telling the truth” and “protecting peace.” Defending international law and defending peace are not opposing choices—they are the same foundation. Telling the truth with evidence and legal grounding is a way to reduce the risk of war, not to provoke war.

What Cambodia needs most now is psychological strength, national unity, and information discipline. In modern conflict, information can become a weapon. That is why defending principles and thinking rationally is itself a form of national defense.

We may be in pain—but we will not fall.

We may be wounded—but we will not surrender.

We may face pressure—but we will not allow threats to force our nation into silence or quiet defeat.