(Phnom Penh): As restaurants in Bangkok grow quieter, hotel rooms remain unfilled, and small businesses begin to close their doors, a troubling question is emerging quietly within the ASEAN community: Why has a country once proud to call itself an “Asian economic tiger” begun to display the symptoms of a regional patient?

This question is not driven by political emotion or rhetorical exaggeration. Rather, it arises from clear signs of decline in commercial capacity, market confidence, and social livelihoods—signals that domestic and international media have increasingly documented in their reporting on Thailand.

A Pre-Existing Economic Illness, Worsened by Political Conflict

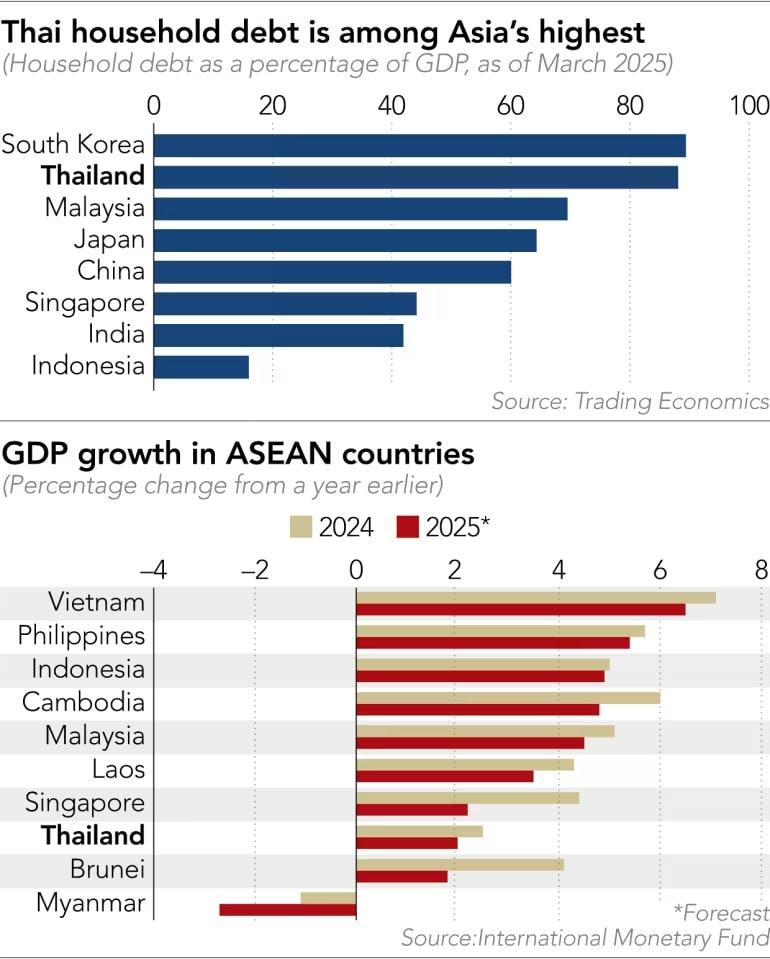

For many years, Thailand’s economy has shown persistently slow growth compared with its Southeast Asian neighbours. High household debt, heavy dependence on tourism, and prolonged delays in structural reform have left domestic production and consumption stuck in a condition best described as “surviving, but not thriving.”

This assessment aligns with reporting by the Financial Times, which recently quoted financial analysts from Kasikornbank warning that while Thailand’s economy is “not yet in the ICU,” it could “look much worse if the government fails to address its structural problems in a serious and sustained manner.”

What this analysis makes clear is that Thailand’s core challenge is not a short-term crisis that can be resolved quickly, but rather a chronic and long-term illness requiring deep treatment and long-range political decisions. Yet persistent political instability—frequent changes in leadership, blocked electoral outcomes, and governments unable to implement long-term reforms—has made such treatment increasingly difficult. In this context, radical nationalist sentiment has not only diverted attention from fundamental problems but has also weakened the state’s own capacity to address an illness it knows it already has.

Tourism Is “Sputtering,” with Ripple Effects Across the Economy

Tourism, long one of Thailand’s most important economic engines, is also showing visible signs of weakness. According to the Financial Times, Thailand welcomed approximately 32.9 million foreign visitors in 2025, a decline from the previous year and still well below pre-pandemic levels.

This downturn has not been confined to tourism alone. Its effects have rippled across related sectors, including retail, agriculture, and hotel construction. Reports of under-occupied restaurants and shuttered small businesses across Bangkok are not anecdotal impressions, but social indicators of declining domestic confidence and shrinking consumer spending power—conditions that make economic recovery even more difficult.

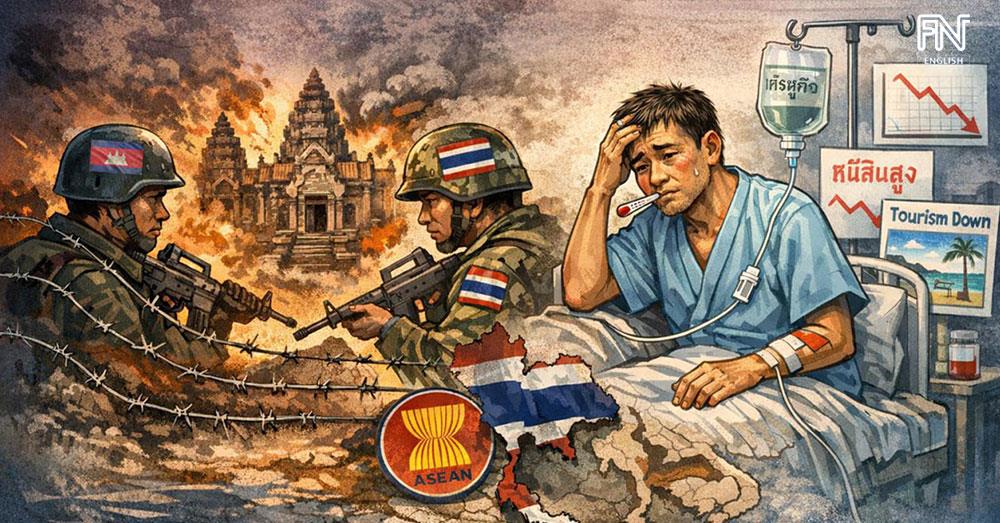

Political Conflict with Cambodia: Populist Politics, Not the Root Cause

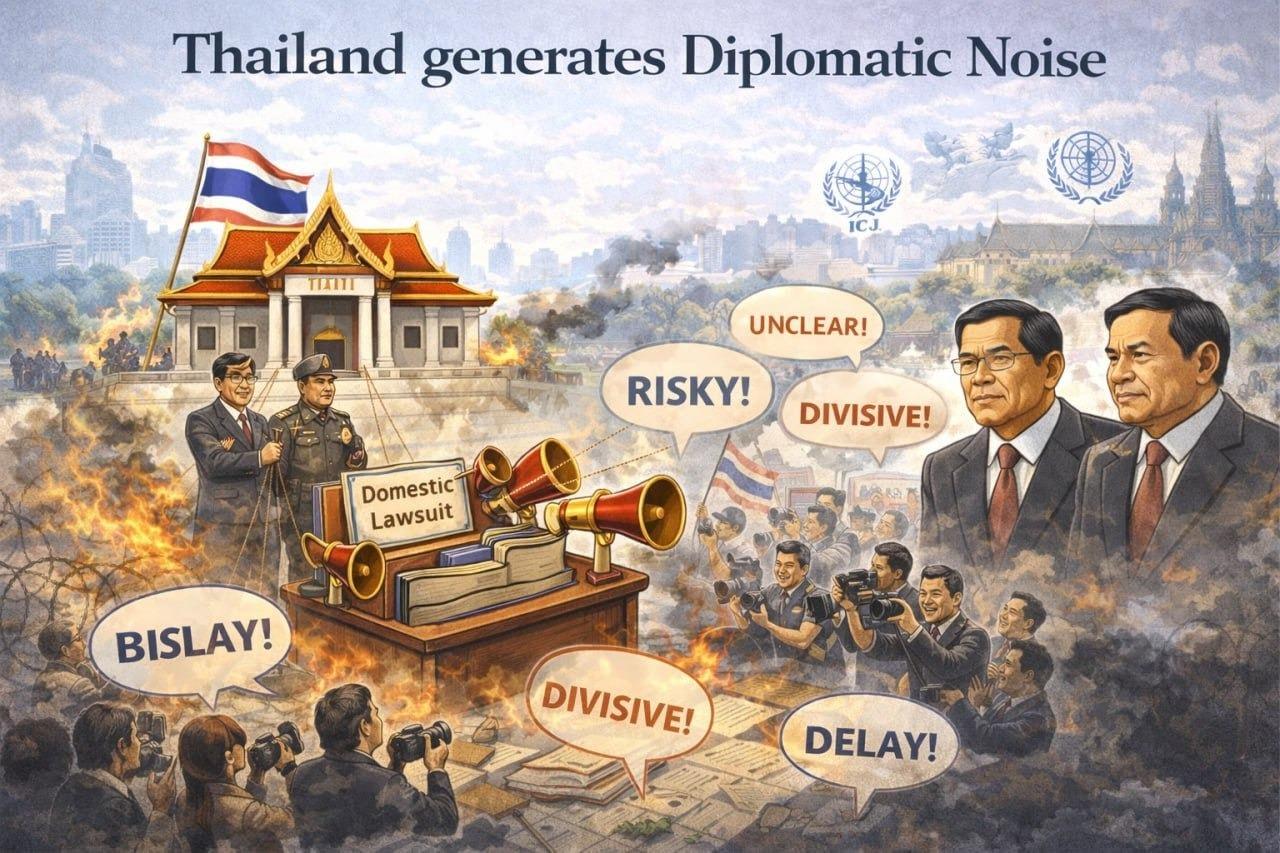

Political tensions with Cambodia are not the root cause of Thailand’s economic problems. However, in a context of slowing growth, public frustration, and delayed reform, such tensions have become a tool of populist politics, intensifying existing structural weaknesses.

Using border disputes as political instruments may temporarily boost nationalist sentiment, but the economic cost is significant. Investor confidence suffers, and Thailand’s image as a safe and stable tourism destination is undermined. As Reuters has reported repeatedly, financial markets and investors tend to exercise heightened caution whenever Thailand experiences political tension and uncertainty.

Put plainly, external conflict does not cure internal problems. Instead, it creates new pressures that accelerate the spread of existing economic and political illness, making recovery more difficult and more costly.

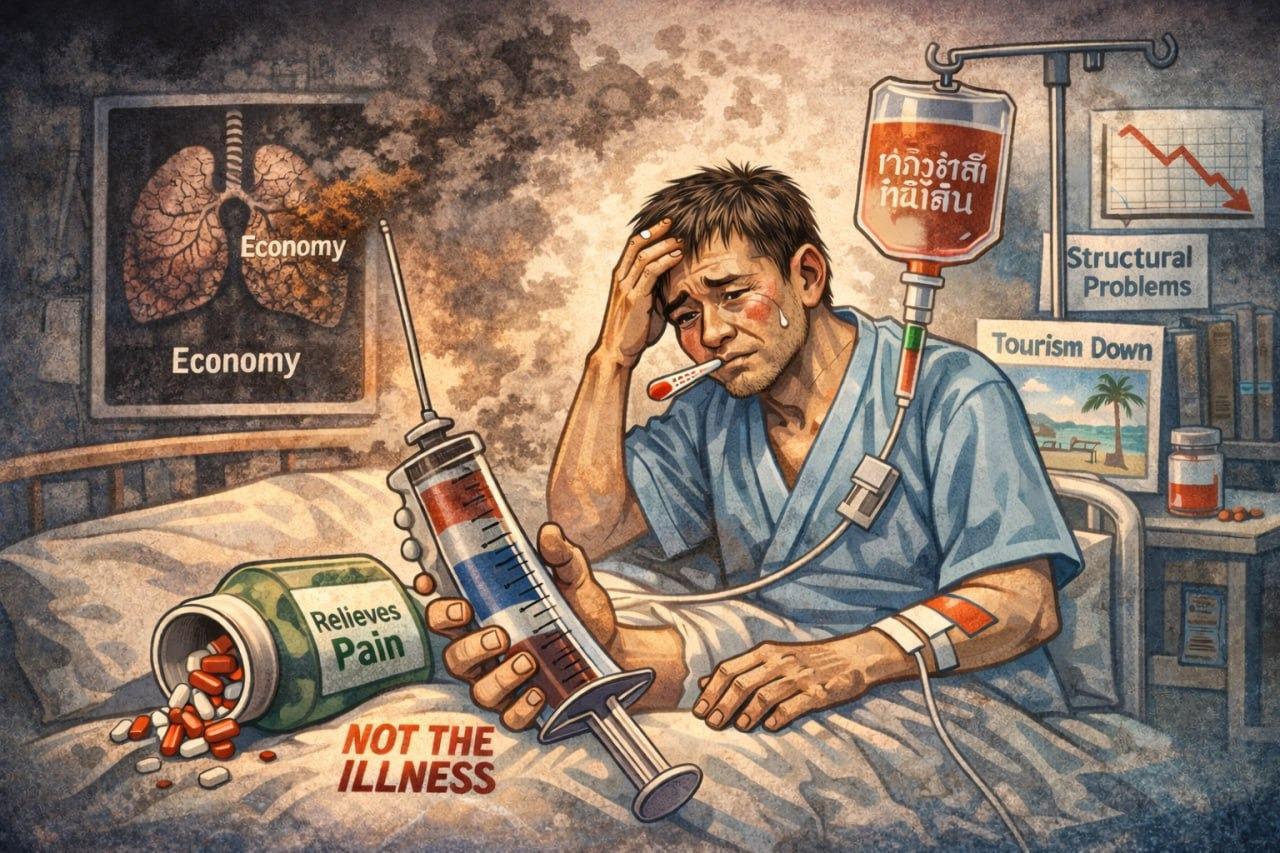

Political Nationalism: Pain Relief Without a Cure

During election seasons, nationalist rhetoric can help politicians secure short-term support. But for Thailand, using conflict with Cambodia as a political stepping-stone functions much like a painkiller—temporarily easing social discomfort without treating the underlying disease.

Even if a political party succeeds at the ballot box by mobilising radical nationalist sentiment, such victories do not resolve the country’s chronic economic illness. On the contrary, delays in reform and continued regional tension deepen structural problems and make them harder to treat over time.

In the end, a country may win an election yet lose investor confidence, long-term economic prospects, and regional standing. For Thailand, continued reliance on nationalist politics risks accelerating the erosion of its once-proud image as an Asian tiger.

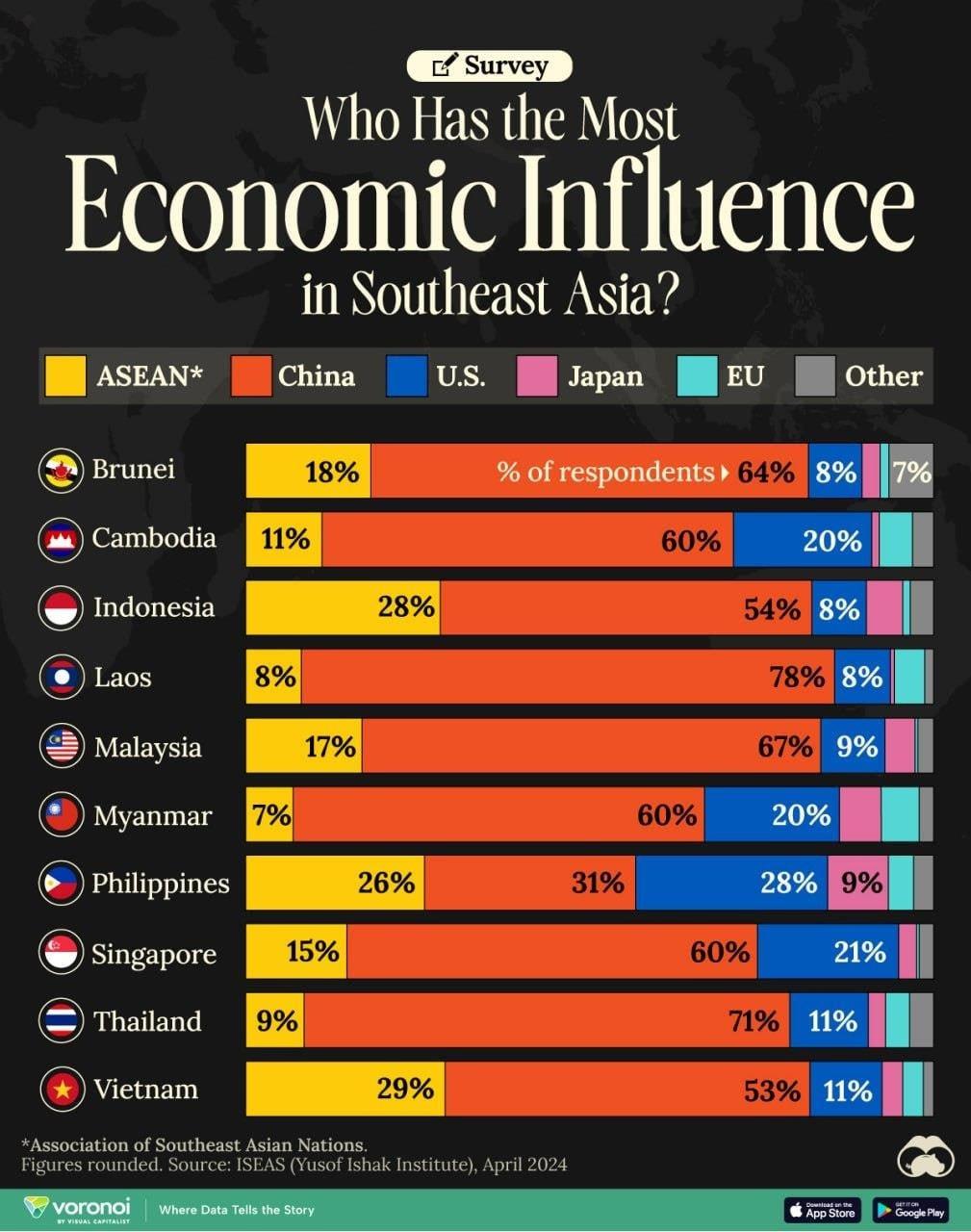

Thailand is a core member of ASEAN. When such a central country remains unwell—due to delayed reforms and persistent political tension—the consequences extend beyond national borders. ASEAN’s credibility and image in the eyes of the international community are inevitably affected.

Conclusion

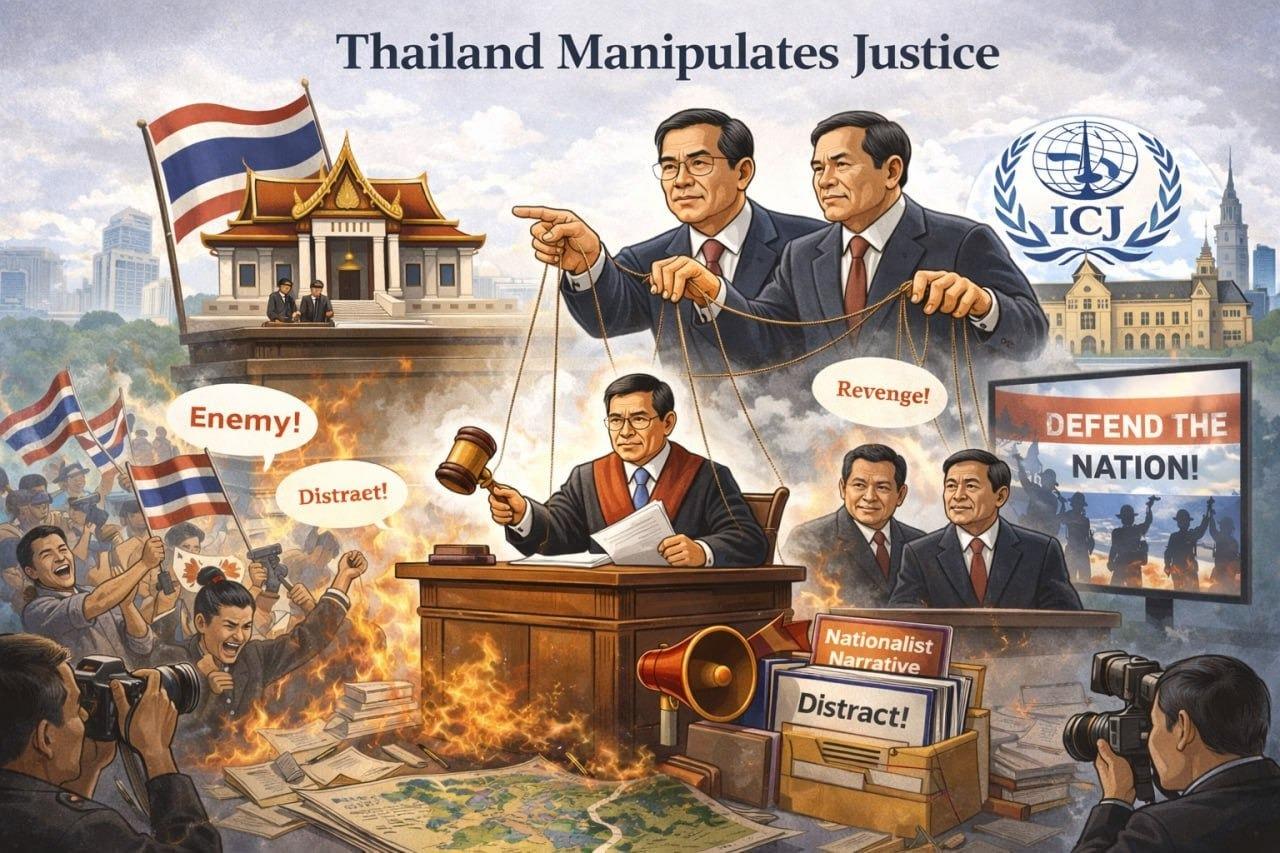

The phrase “ASEAN’s sick man” is not a label directly used by the Financial Times or Reuters. Nevertheless, the economic, social, and political signals documented by these international sources point unmistakably to a condition of chronic illness within Thailand—one that will worsen if the country continues to postpone treatment of its long-standing internal problems.

Thailand is not becoming a regional patient because of its conflict with Cambodia alone. It is becoming one because of its own political choices—choosing to use external conflict as a distraction while delaying the difficult work of internal reform. Conflict may deliver short-term political gains, but for the nation’s future it only makes a long-standing illness more severe, more expensive, and far harder to cure.