(Phnom Penh): History is not merely a record of the past; it is a mirror that reflects the future. At every stage when Thailand has attempted to exploit power—or power vacuums—to encroach upon Cambodian territory, it may have appeared to gain ground temporarily. Yet, time and again, it has ultimately lost on a higher plane: the plane of international law and legal legitimacy.

The second stalemate at the Regional Border Committee (RBC) meeting on February 2, 2026, is therefore not a sign of diplomatic exhaustion. Rather, it signals that Thailand’s long-standing strategic pattern is colliding with a modern legal order—one in which unlawful power on the ground can no longer override international law.

From the Past to the Present: An Old Pattern That Repeatedly Returns

From the late 18th century through the 20th century, history records numerous moments when Siam took advantage of Cambodia’s internal weakness or international instability to seize and occupy Cambodian territory. Yet history also records a consistent outcome: whenever these disputes were brought before treaties or international legal mechanisms, territory taken through force and opportunism was ultimately compelled to be returned to its rightful owner.

In the 21st century, despite profound changes in the global order, this strategic pattern has not disappeared. Only its form has evolved to suit a new era.

Historical scholarship documents that in 1794—prior to French colonial involvement—Siam exploited Cambodia’s vulnerability to take control of Battambang and Siem Reap provinces, including the Angkor region, holding them for more than a century. This occupation was not accidental but part of a calculated strategy rooted in regional instability and Cambodian weakness.

During the French colonial period, however, the need to establish clear borders in accordance with international principles led France to compel Siam to sign the 1904 and 1907 treaties. As a result, those provinces were returned to Cambodia. From these treaties emerged the Annex I Map, which clearly placed the Preah Vihear Temple within Cambodian sovereign territory.

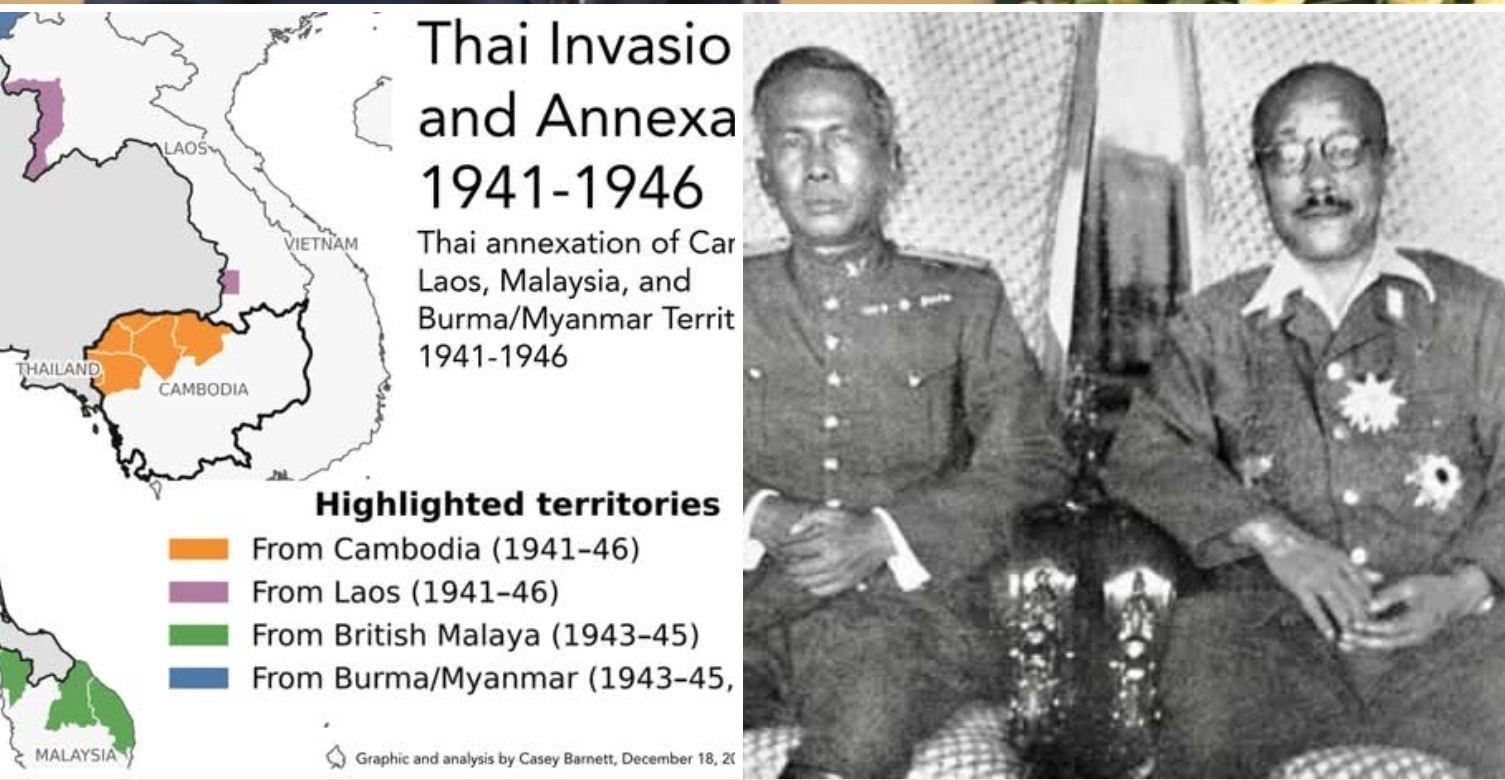

Later, during World War II between 1941 and 1946, when Imperial Japan dominated the region, Thailand collaborated with Japan to force France into signing the 1941 Tokyo Convention, reclaiming Battambang and Siem Reap. This was yet another instance of exploiting wartime power vacuums to pursue territorial ambition.

However, once the war ended in 1946 and international order was restored, France and the United States jointly exerted pressure on Thailand. The United States refused to recognize the wartime territorial transfers, and France compelled Thailand to sign the 1946 Settlement Agreement. This agreement annulled the Tokyo Convention in its entirety and required Thailand to return the territories to Cambodia. This legal foundation permanently invalidated any Thai claim based on wartime circumstances.

Delay as Strategy in the 21st Century

Today, seeking to avoid the legacy of past legal defeat, Thailand has adopted a familiar tactic: delay. By invoking various pretexts and refusing to allow border disputes to confront international legal forums, Thailand seeks to “buy time” while continuing to manufacture facts on the ground.

Yet the fundamental difference between past and present is this: in the 21st century, time no longer erases evidence—it accumulates it. What Thailand perceives as a defensive strategy is increasingly becoming documented proof of an unwillingness to resolve disputes peacefully and lawfully. When justice is eventually called upon to adjudicate, this recurring pattern will meet the same fate history has already delivered—Thailand cannot escape international law.

The February 2, 2026 RBC Meeting: A Second Stalemate with Deeper Meaning

The Secretariat-level meeting of the Regional Border Committee (RBC) between Cambodia’s Military Region 4 and the Thai side, held at the Choam–Sa Ngam International Crossing in Oddar Meanchey Province on February 2, 2026, under ASEAN observation, concluded without identifying common ground. Both sides agreed to return to their respective headquarters to continue exchanging documents and discussions. This marked the second such stalemate following earlier deadlock.

The significance of this outcome lies not in the phrase “no agreement,” but in how the stalemate was recorded:

- It occurred under ASEAN observation, elevating the issue from a purely bilateral matter to one of regional concern;

- It was grounded in the spirit of the Joint Statement of the General Border Committee (GBC), reaffirming commitments to peaceful and legal mechanisms;

- And it was formally documented, creating records that may serve as legal references in the future.

In the language of international politics and law, refusal and delay are no longer silence. They are records—records that reflect either commitment or the lack thereof to lawful, peaceful dispute resolution.

The 21st Century: When a “Third Historical Humiliation” Becomes Possible

Historical humiliation does not arise from losing battles on the battlefield, but from being compelled to retreat in forums one has long sought to avoid. In the 21st century, the conditions for a third such humiliation are steadily taking shape:

- A growing archive of documented refusals and delays;

- Increasing regional and multilateral scrutiny;

- And the tightening grip of international legal language and standards.

When a conflict is transformed from “weapons on the ground” into “liabilities on record,” the power of denial becomes evidence against itself.

In previous eras, Thailand did not merely administer occupied Cambodian territory—it constructed infrastructure to create the illusion of permanence. Yet once international law reasserted itself, those structures failed to legitimize occupation. Territory was returned, and the constructions became historical scars of a failed strategy.

Today, similar patterns are re-emerging in new forms: fencing, land encirclement, demolition of civilian homes, and attempts to erase physical evidence—classic efforts to create faits accomplis. But the modern world no longer functions as it once did. Destroying evidence on the ground cannot erase evidence in documents. Time does not absolve violations; it records them.

History has already delivered this lesson twice. Territorial absorption and illegal construction do not yield lasting victory. When justice arrives, Cambodia will not only recover its land, but the violator will face legal liabilities arising from those violations. Illegal structures on Cambodian soil cannot be taken back—they remain evidence of wrongdoing, not lawful property.

Conclusion

The second stalemate of the February 2, 2026 RBC meeting is not a sign of Cambodian weakness. It is evidence that Cambodia is rejecting the games of the past and deliberately shifting the dispute to a forum where power on the ground cannot defeat the authority of law. If Thailand continues to rely on outdated strategies in a world that has fundamentally changed, a “third historical humiliation” is no longer a question of whether, but when. Justice is never lost—even when its journey is slow.