(Phnom Penh): In a world where international law was built to restrain war and settle disputes peacefully, some states still choose a different path—one that is not grounded in justice, but in the use of domestic “legal theater” to serve political objectives and prolong conflict. Thailand’s move—through a senior official—to file a domestic legal complaint against Cambodia’s top leaders is a clear illustration of that political play.

Cambodia’s official protest, issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, was not an emotional reaction. It was a direct and formal assertion that Thailand’s lawsuit is inconsistent with international law, contrary to the ASEAN spirit, and at odds with efforts to reduce tensions following the 2025 ceasefire. The key question, therefore, is not simply, “Can Thailand sue?” but rather: Why did Thailand choose its own courts instead of an international forum?

Cambodia’s Official Protest

According to Cambodia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Thailand—through the Secretary-General of its National Security Council—filed a legal complaint against Samdech Techo Hun Sen, President of the Cambodian Senate, and Samdech Moha Borvor Thipadei Hun Manet, Prime Minister of Cambodia, claiming the case concerns “military operations along the Cambodia–Thailand border in 2025.”

In response, Cambodia’s Foreign Ministry submitted an official protest letter dated January 29, 2026, stating that the complaint against Cambodia’s top leadership runs counter to continued efforts to ease tensions between Cambodia and Thailand and contradicts the spirit of the Joint Statement of the 3rd Special Meeting of the General Border Committee, held on December 27, 2025.

The ministry’s letter stated:

“This legal action is inconsistent with the purposes and principles of the ASEAN Charter and the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia. Any attempt to initiate domestic legal proceedings targeting senior leaders of a sovereign state for acts connected to their official duties—especially acts relating to national defense and territorial integrity—has no legal basis under international law.”

Under international law, acts carried out by a head of state or head of government in the exercise of official state duties—particularly those related to national defense and territorial integrity—are considered acts of state. Such acts are protected by immunity, and therefore cannot be adjudicated by the domestic courts of another state. In this context, using a domestic court to target senior leaders of another sovereign state not only violates the principle of sovereign equality, but also contradicts the established commitment—within ASEAN and international law—to resolve disputes peacefully.

Thai Domestic Courts: A Forum Thailand Can Control

Thailand’s decision to pursue a case in its domestic courts is neither accidental nor purely legal in nature. Rather, it is a strategic choice that allows Thailand to control the forum, the narrative, and the political meaning of the case.

In this environment, law is not treated as an independent instrument for impartial justice. It is repurposed as a political tool—used to amplify nationalist sentiment and to relieve internal political pressure. For the Thai public, the case can be framed as: “The government is using the law to defend the nation and sovereignty,” even though, in practice, such courts hold no authority over Cambodia or over senior leaders of another sovereign state. This kind of narrative management also diverts public attention away from realities on the ground and from the international-law questions Thailand cannot confidently address in an international forum.

Why Thailand Avoids the International Court of Justice

If Thailand truly trusted impartial justice and sought a genuine legal resolution under international law, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) would be the most appropriate first choice. Yet Thailand has not taken that path—because it understands that an international forum cannot reliably deliver outcomes aligned with its political objectives.

First, under international law, Cambodia’s top leaders enjoy full immunity for official acts of state, especially actions related to national defense and territorial integrity. This principle prevents international proceedings from being converted into a courtroom for judging individuals for such state acts.

Second, credible facts on the ground—ranging from the use of heavy weapons, alleged incursions, and large-scale displacement—could place Thailand at risk of shifting from “plaintiff” to respondent, if a dispute were tested before an international forum that prioritizes evidence and legal principles over political messaging.

Third, Thailand’s past defeats in the Preah Vihear Temple case—in 1962 and the Court’s further clarification in 2013—remain a deep political scar. Those rulings demonstrated that international adjudication does not follow political pressure or public emotion; it is driven by maps, documents, and legal doctrine—factors Thailand cannot control in the way it can manage domestic proceedings.

For these reasons, Thailand’s avoidance of an international court is not random. It is an avoidance of a venue where it cannot control the outcome. In that context, the domestic court becomes the most politically useful instrument—allowing Thailand to prolong the dispute through what Cambodia describes as “legal maneuvering” rather than a peaceful settlement grounded in international legality.

What Game Is Thailand Really Playing?

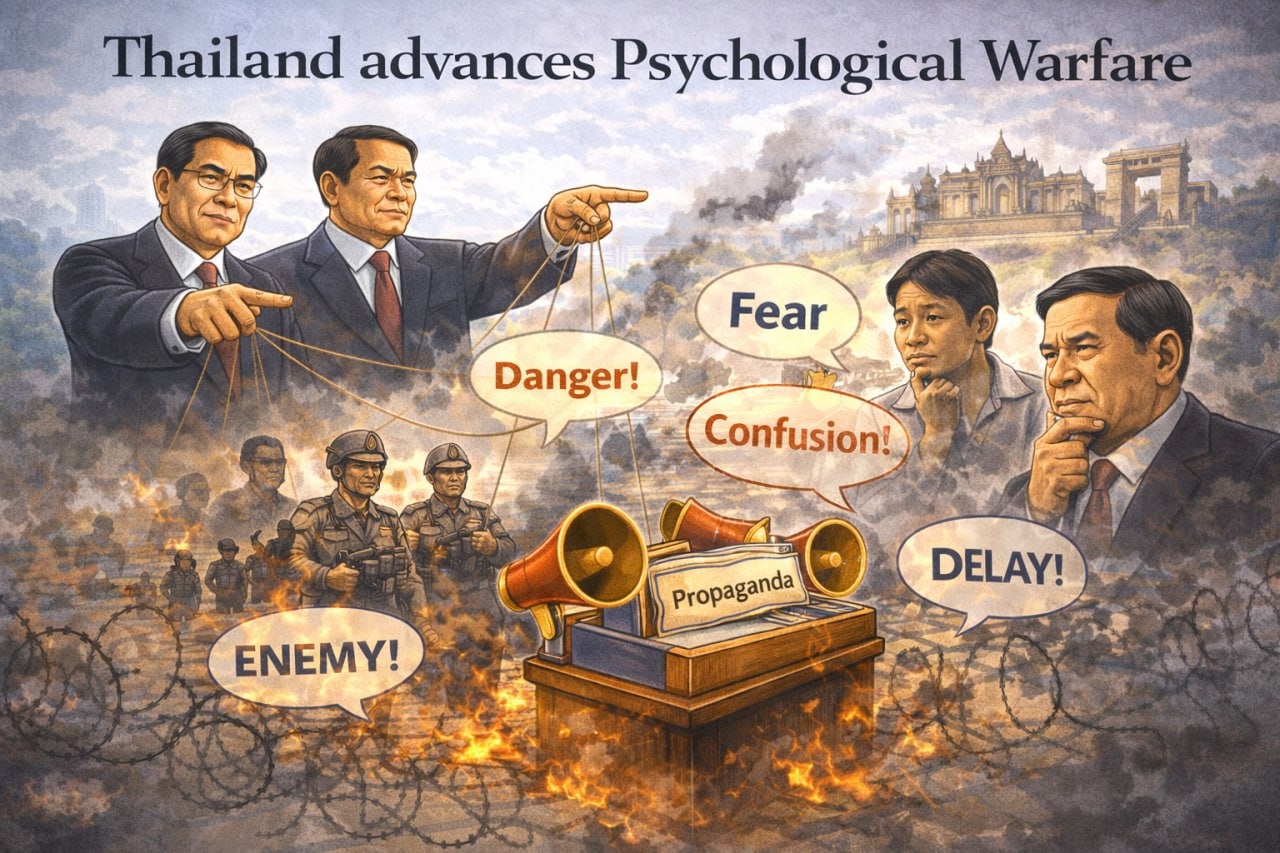

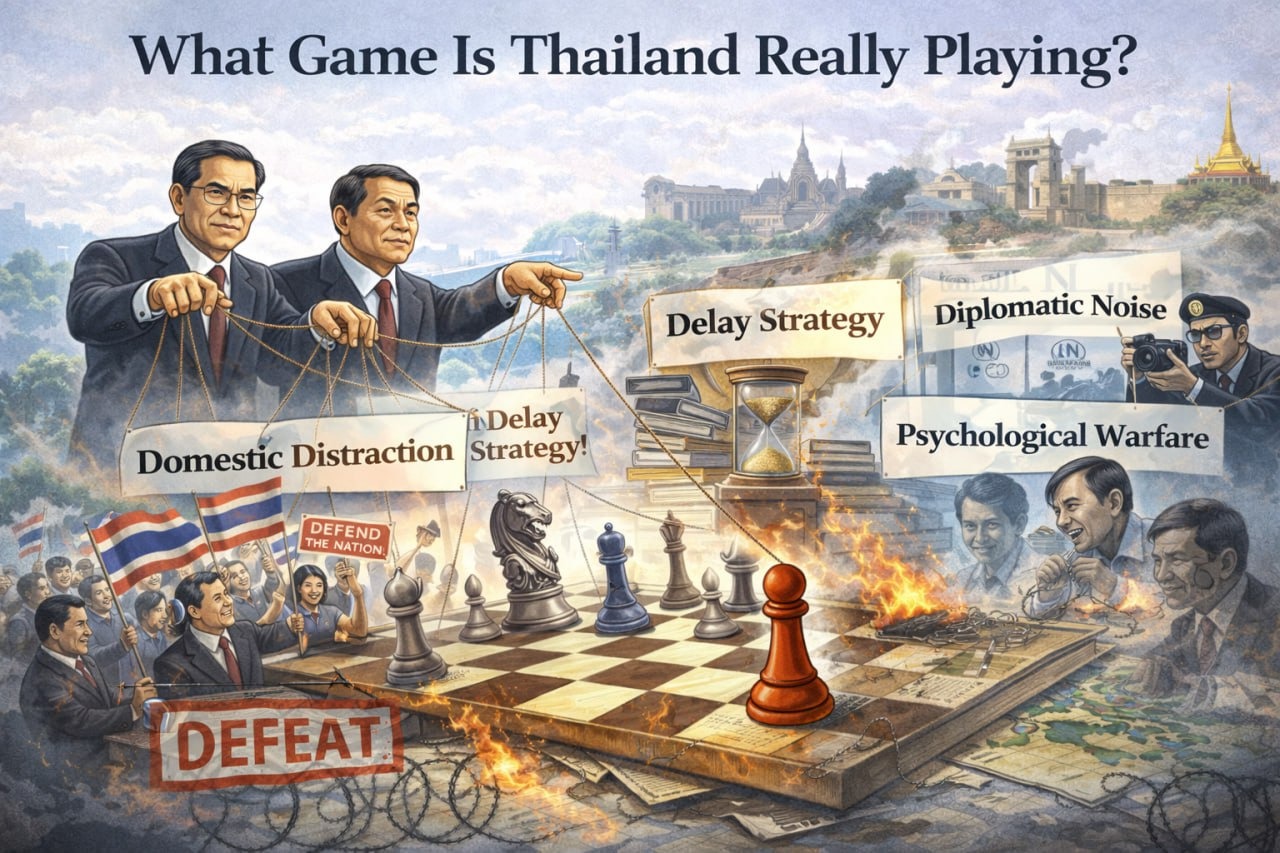

Beneath the language of legal procedure, this case is best understood not as a pure search for justice, but as a multi-layered political strategy serving Thailand’s domestic and international aims.

First, Thailand employs Domestic Distraction, using its courts to redirect internal political heat toward an external “enemy,” shaping a narrative that the government is “using the law to defend the nation and sovereignty.” This helps stabilize domestic politics and reduce pressure from nationalist forces and other power centers.

Second, Thailand applies a Delay Strategy—initiating legal steps that are unlikely to produce a definitive result, but effective in slowing the peace process, creating uncertainty, and disrupting the implementation of ceasefire arrangements and de-escalation mechanisms previously agreed by both sides.

Third, Thailand generates Diplomatic Noise, using the existence of a domestic case to muddy the picture internationally and make the dispute appear complex and ambiguous—encouraging third countries to hesitate, reducing the pressure that would otherwise fall on Thailand.

Fourth, Thailand advances Psychological Warfare, seeking to create long-term doubt, fear, and tension—both within Cambodian society and across diplomatic arenas—undermining confidence and prolonging conflict without the need for military escalation.

For these reasons, Thailand’s domestic lawsuit cannot be treated as a legal matter alone. It is politics wearing legal clothing—an example of lawfare used to prolong conflict, delay peace, and weaken the standing of international legal norms, while Cambodia continues to position itself on the platform of justice, peace, and international law.

Conclusion

Thailand’s decision to sue Cambodia in Thai domestic courts is not a pursuit of justice. It is the use of “law” as a political instrument to sustain a conflict that Thailand cannot win—either by force or by international law. The move makes clear that Thailand has chosen a political route dressed in legal attire, primarily to buy time, create disruption, and keep the dispute in a state of uncertainty.

By contrast, Cambodia presents itself on a higher platform: justice, peace, and international legality. In an era when law can be turned into a weapon, the true winner is not the one who files the loudest lawsuit, but the one who stands with truth, patience, and time—the very standards by which history ultimately delivers its verdict.