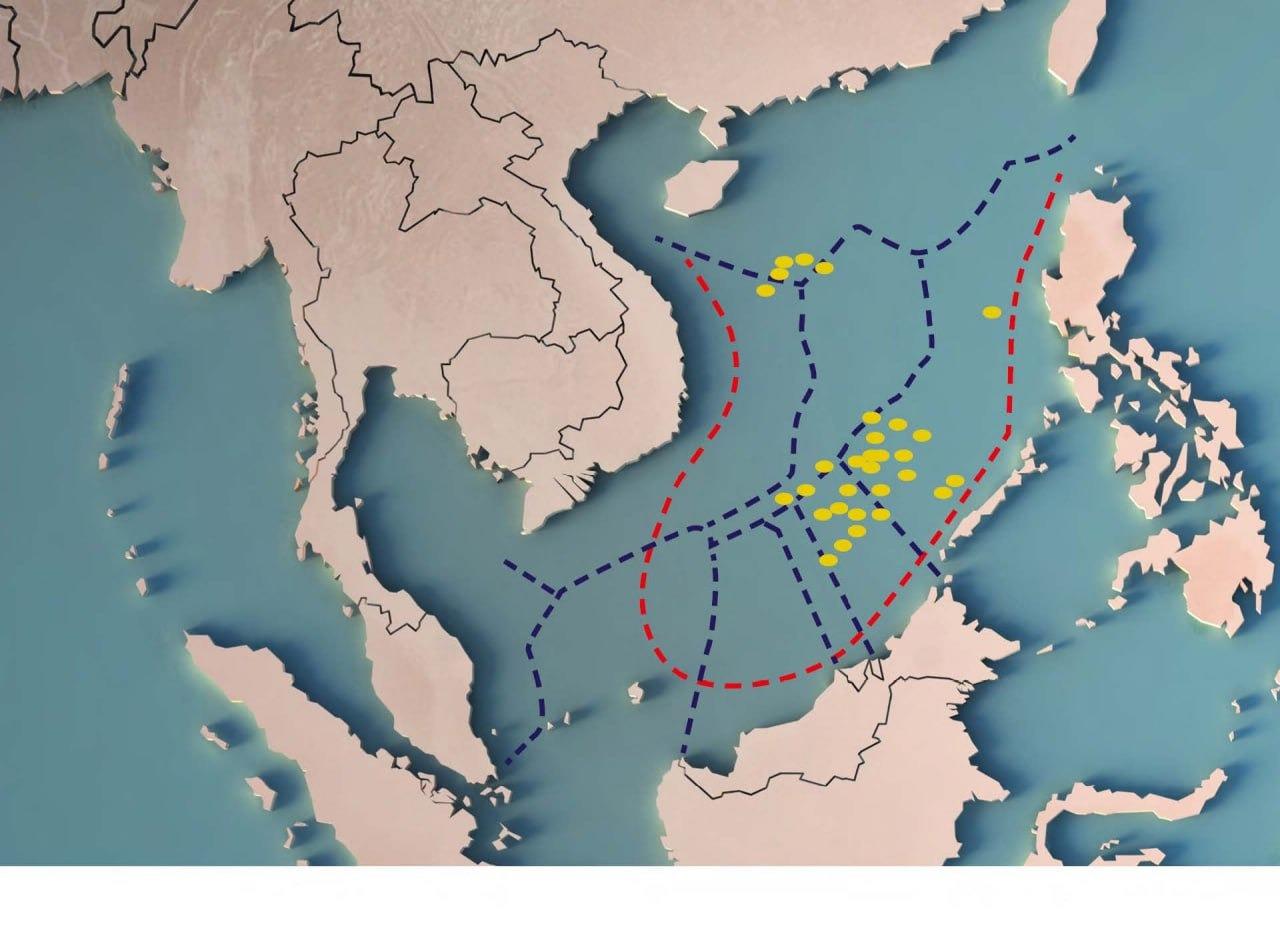

(Phnom Penh): In a world where war and conflict are increasingly becoming defining challenges of the century—whether in Europe, the Middle East, or Southeast Asia—a quiet yet weighty question is being posed to the international community: are existing global peace structures sufficient to respond to the complexities of modern conflict?

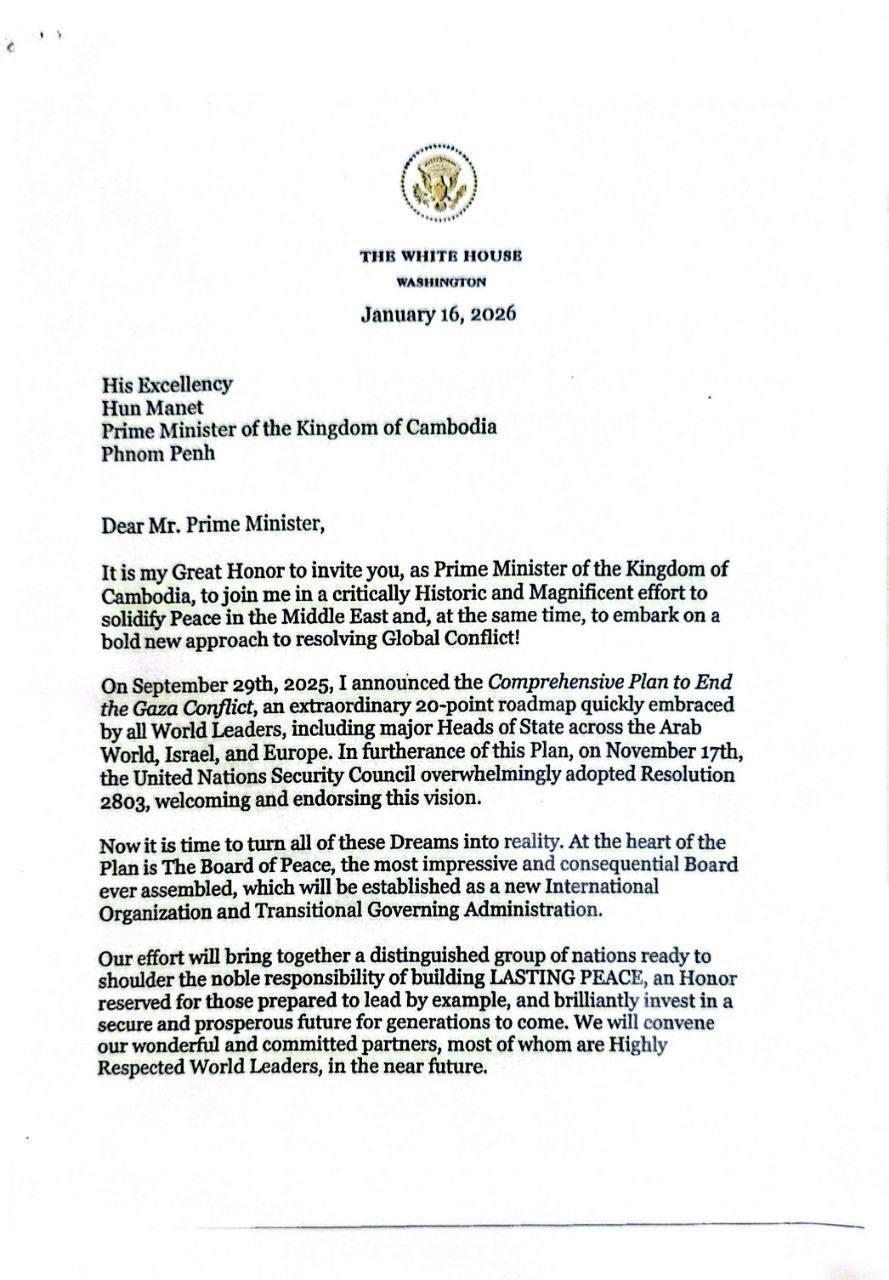

Amid the search for answers, a new concept has emerged under the name “the Board of Peace.”

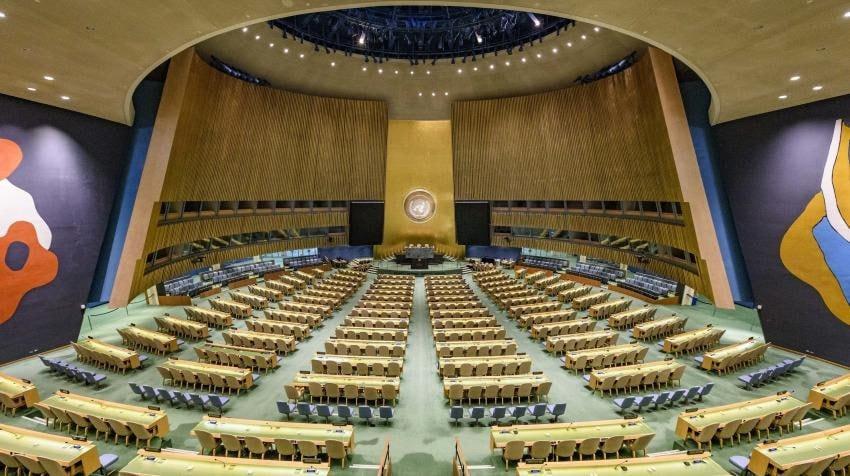

The Board of Peace is an idea raised within the context of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2803, adopted to support the Gaza peace initiative and post-conflict transitional governance. Its stated objective is to coordinate peacebuilding and stabilization efforts in situations where certain conflicts are viewed as exceeding the practical capacity of traditional international mechanisms.

For smaller states such as Cambodia, this emerging concept is not merely an international peace issue; it represents a strategic question that requires careful and measured consideration.

What Is the Board of Peace?

According to available descriptions, the Board of Peace is conceived as a transitional governance mechanism designed to facilitate the shift from armed conflict to peace. Its purpose is to fill gaps where traditional international institutions may be constrained by time, mandate, or operational limitations.

However, the Board of Peace is not a United Nations body, nor does it possess the same legal standing as the UN. Even though it is referenced in the context of a UN Security Council resolution, it remains a distinct and separate initiative.

The Role of the United States in Promoting Peace

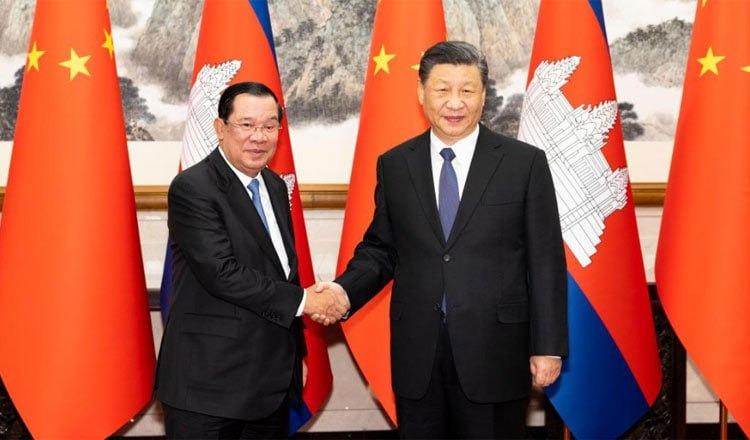

It is difficult to dispute that the United States plays a significant role in promoting peace and deterring the spread of international conflict. For smaller countries, U.S. engagement and influence can be critical factors in preventing aggression and maintaining regional stability.

At a time when Cambodia faces external security pressures and unresolved territorial challenges, maintaining constructive and functional relations with the United States remains a strategic necessity. U.S. influence continues to matter not only in global forums but also in shaping regional calculations and helping to prevent further escalation of conflict.

In this context, Cambodia’s ability to sustain stable and constructive relations with the United States cannot be overlooked as a key strategic consideration.

Questions and Ongoing Debates Surrounding the Board of Peace

Although the peace objectives of the Board of Peace have been clearly articulated, the initiative continues to generate extensive debate within the international community. Some observers have raised concerns about legal ambiguity between this new mechanism and the United Nations Charter, as well as about potential financial burdens and governance structures that could raise questions about balance and equity in the international system.

These discussions do not amount to a rejection of peace initiatives. Rather, they reflect a broader demand for clarity, transparency, and coherence with established international norms—particularly for countries that rely on international law as a protective shield rather than on raw power.

The $1 Billion Question: Financial Commitments and Controversy

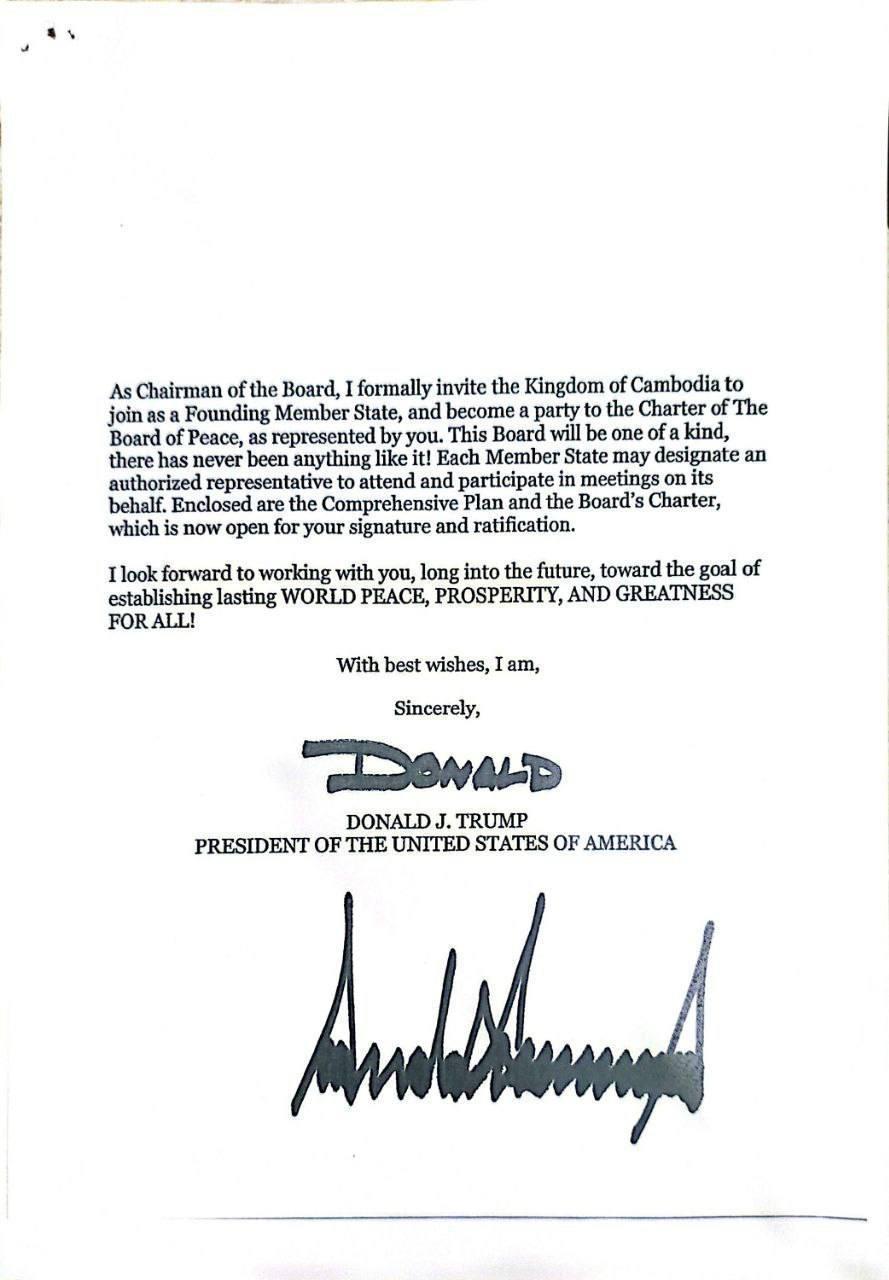

Among the most debated issues surrounding the Board of Peace is the question of financing, especially claims related to a US$1 billion contribution allegedly associated with participation.

From an official standpoint, UN Security Council Resolution 2803 does not stipulate any fixed financial obligation for states wishing to engage with the Board of Peace. The resolution does not require any country to pay US$1 billion to become a member. Instead, it refers only to voluntary contributions and donor-based funding intended to support peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction.

The controversy arose following reports of draft charter provisions and internal discussions suggesting that states seeking long-term or enhanced roles—such as founding or permanent status—may be encouraged to make substantial financial commitments toward reconstruction and stabilization efforts.

Some view this approach as a pragmatic means of mobilizing resources rapidly in severely affected post-conflict zones. Others, however, express concern that it could foster a perception of “paying for influence,” potentially diverging from the multilateral and egalitarian principles traditionally upheld by the United Nations.

For smaller states like Cambodia, this debate extends beyond financial considerations. It raises broader strategic questions about economic capacity, national interest returns, and the long-term diplomatic implications of participation in high-cost international mechanisms.

Cambodia’s Strategic Balance

For Cambodia, support for peace cannot be separated from the protection of national interests. At a time when the country continues to face persistent security challenges and regional instability, diplomatic balance is not a luxury—it is a necessity.

Accordingly, participation in any new international mechanism must be evaluated carefully through multiple lenses: respect for international law, the central role of the United Nations, economic sustainability, and the ability to maintain strategic flexibility in relations with major powers.

In this context, supporting peace initiatives in principle does not automatically require institutional participation in practice. Instead, careful scrutiny is essential to ensure that any engagement aligns with Cambodia’s national interests and broader strategic environment.

Conclusion

Throughout its diplomatic history, Cambodia has consistently supported peace efforts grounded in international law and the central role of the United Nations. As new ideas and mechanisms emerge, cautious engagement, diplomatic balance, and demands for clarity remain the safest path for smaller states navigating an international system marked by intensifying power competition.

In this sense, support for peace as a principle must be assessed comprehensively—particularly whether implementation requires automatic institutional alignment with newly created mechanisms. For Cambodia, sustainable peace is peace that strengthens international law, preserves national sovereignty, and allows the country to make independent decisions within an increasingly complex and rapidly evolving global environment.