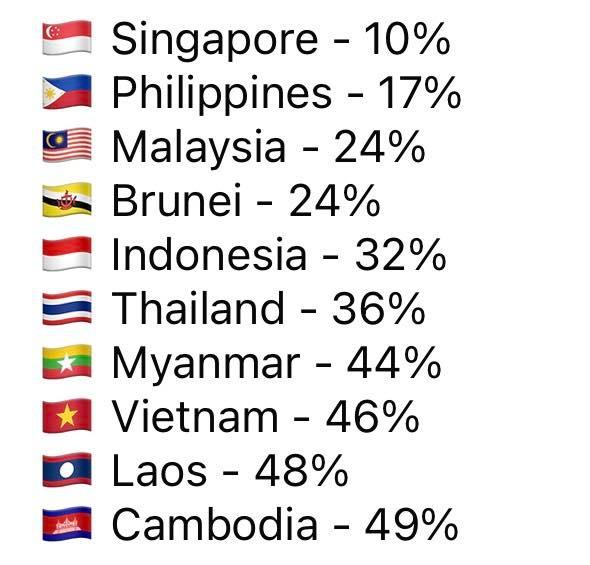

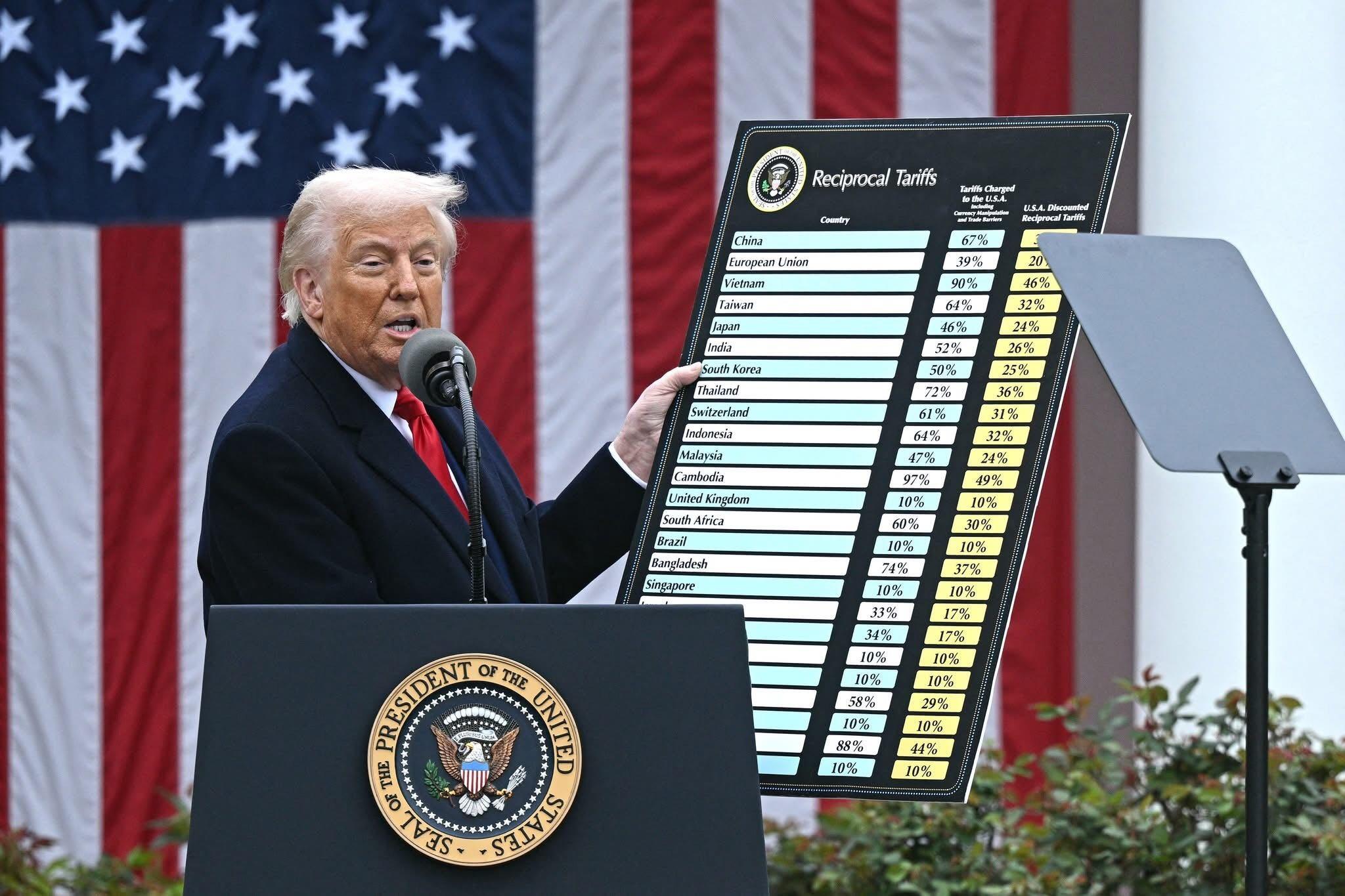

(Phnom Penh): In today’s global trading system, tariffs are no longer merely economic costs; they have become powerful political instruments. For a small country like Cambodia, a 49% tariff is not just a figure on paper—it is a red line that could abruptly cut factory jobs, disrupt production, and shake broader social stability. In that narrow space of risk, Cambodia’s reciprocal trade agreement with the United States emerged not as a luxury option, but as an urgent response.

In August 2025, Cambodia decided to allow U.S.-made goods to enter the Cambodian market duty-free, aiming to reduce the risk posed by U.S. “reciprocal tariffs” that threatened Cambodia’s export-driven economy. Although the agreement has been viewed by some as tilted toward the United States, it underscores a central reality of modern trade: it is now a strategic contest shaped by market power, governance standards, and geopolitics.

An Economic Lifeline, Not a Routine Concession

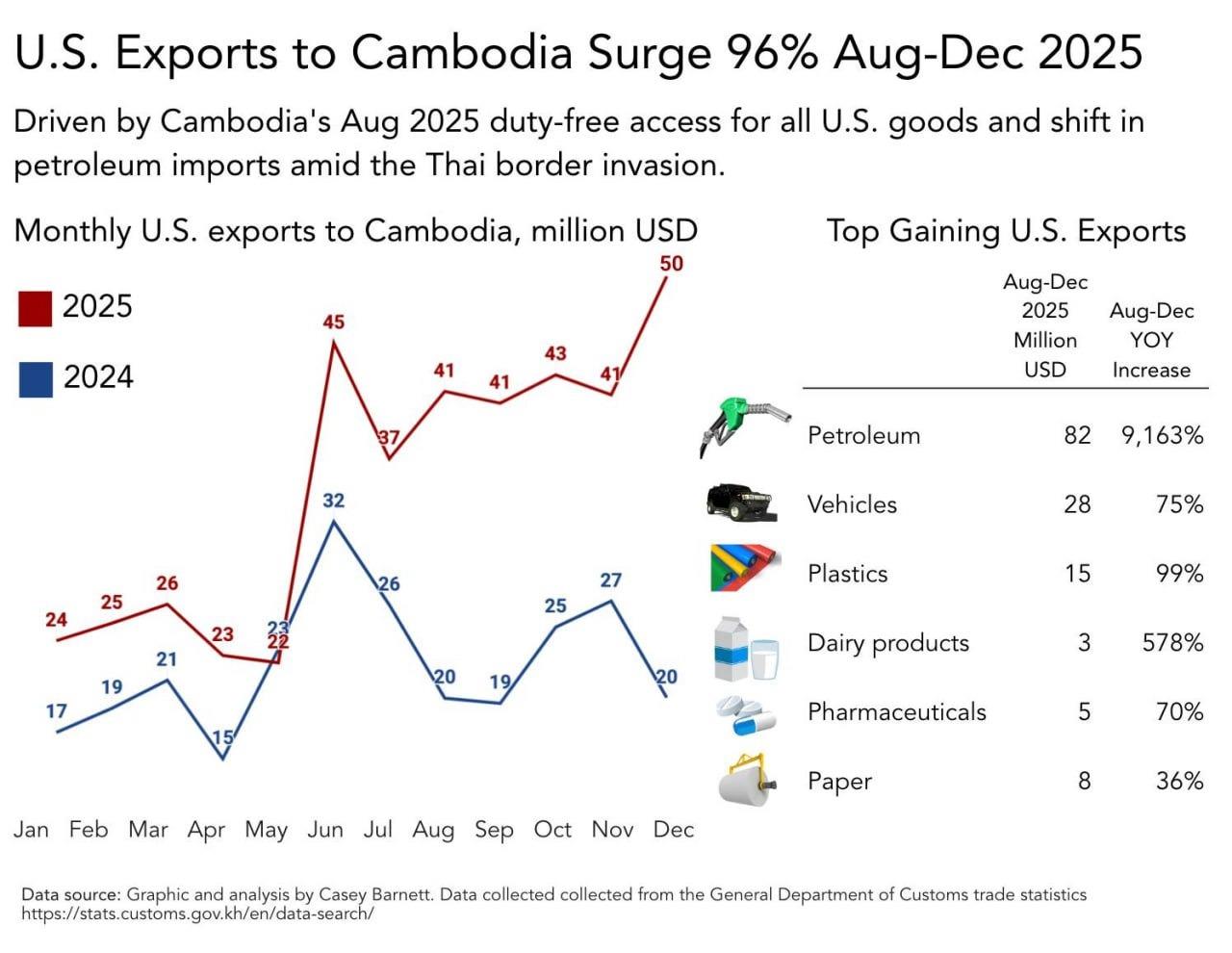

The President of the American Chamber of Commerce in Cambodia, Casey Barnett, wrote that following this policy change, U.S. exports to Cambodia increased by 96% year-on-year over the period from August to December. This growth occurred across 54 out of 85 product categories, highlighting the agreement’s real-world impact. Most notably, imports of refined petroleum products rose ninefold, a clear signal that the agreement is not merely political language on paper—it is producing measurable outcomes.

The United States is Cambodia’s largest market, absorbing about 38% of Cambodia’s total exports. In this context, the threat of tariffs as high as 49% meant Cambodia’s garments, footwear, and other industrial exports could lose competitiveness almost immediately. Cambodia therefore chose to use its own market as an instrument of trade diplomacy—to protect workers’ livelihoods, safeguard industrial stability, and defend the national economy as a whole.

At the same time, the surge in U.S. imports was also driven by de-risking—a deliberate shift away from dependence on fuel products from Thailand, at a time when Thailand’s aggression and instability affecting Cambodia have continued. In this setting, trade is not only about price; it has become an instrument of economic security and national security.

Duty-Free U.S. Goods: A Trade-Off to Rescue the Economy

Barnett further noted that in August 2025 Cambodia granted duty-free access for all U.S.-made products as a preferential measure designed to lower exposure to U.S. reciprocal tariffs. This step was taken at a moment when Cambodia faced the prospect of tariffs reaching 49%, a level that could severely threaten export manufacturing and workers’ livelihoods.

Under these conditions, allowing duty-free entry for U.S. goods should not be framed as a surrender of sovereignty. Rather, it reflects a strategy of Defensive Trade Diplomacy—using trade policy to defend Cambodia’s most vital export market and preserve macroeconomic stability.

In practical terms, Cambodia accepted a partial loss of customs revenue to prevent a far greater risk: losing export market access and suffering a breakdown in industrial supply chains. This was a calculation based on power realities and strategic risk, not an emotional political reaction or a simple response to external pressure.

In a world where trade policy is increasingly weaponized, Cambodia’s decision suggests that even small countries can use their own market as a defensive tool—if they negotiate strategically within the constraints of global power.

Tangible Results: U.S. Goods Up 96% in Five Months

Barnett emphasized again that the policy shift produced fast results: U.S. exports to Cambodia rose 96% year-on-year over just five months (August–December). The increase did not occur in only a few items; it spread across 54 of 85 categories, suggesting the agreement affected the broader structure of bilateral trade rather than simply adjusting tariff rates.

The most striking signal was the ninefold increase in refined petroleum imports from the United States. This surge cannot be explained solely by price or short-term demand. It points to a strategic shift in Cambodia’s energy supply chain—an effort to de-risk and reduce reliance on fuel sources linked to Thailand, amid ongoing aggression and instability affecting Cambodia.

These results strongly indicate that the Cambodia–U.S. reciprocal trade agreement has real, operational impact. It is not symbolic politics. It is a policy that has redirected trade flows and directly influenced Cambodia’s economic security and energy security.

Trade and Geopolitics: Diversifying Away from Thailand

Barnett also highlighted that Cambodia has begun shifting certain import sources from Thailand to the United States. For example, imports of some dairy products have moved away from Thailand. Other notable increases in imports from the United States include vehicles, plastics, paper, textile fibers, food products, machinery, and industrial equipment.

This shift is not merely a market-driven adjustment. It reflects a broader de-risking strategy—reducing dependence on a neighboring country that is actively generating conflict and committing acts of aggression against Cambodian territory. When supply chains become vulnerabilities, diversifying import sources becomes a matter of national security, not just economics.

In this sense, trade is no longer simply the buying and selling of goods. It becomes a strategic tool for protecting economic security, energy security, and national stability amid fast-moving geopolitical change.

Unequal Balance and the Reality of Power

In 2024, Cambodia exported USD 12.7 billion worth of goods to the United States, while importing only USD 300 million from the United States. The President of AmCham Cambodia acknowledged directly that the negotiated agreement is tilted and more favorable to the United States—yet that tilt must be understood within an asymmetrical trade structure: Cambodia depends heavily on the U.S. market, while the U.S. does not depend on Cambodia’s market.

Part of the imbalance is explained by Cambodia’s lower purchasing power, which limits the extent to which U.S. goods can become everyday consumer products for most people. Another part stems from licensing procedures and technical requirements that remain insufficiently clear and standardized—creating non-tariff barriers that prevent U.S. products from entering Cambodia’s market smoothly.

In this context, the United States focuses on reducing its trade deficit, while Cambodia focuses on preserving export market access and protecting jobs. This mismatch is not a clash of political emotions. It is a structural conflict between the priorities of a major power that can shape market rules and a smaller state that depends on external markets—one that ultimately defines the direction of trade negotiations and the concrete terms of implementation.

Governance Provisions: U.S. Conditions, Cambodian Gains

The reciprocal trade agreement also requires Cambodia to continue improving governance and institutional credibility. Measures include establishing an independent labor court, publishing draft regulations for public review, clearly disclosing official service fees, and combating fraud and corruption. While these provisions appear as external conditions, their long-term benefits accrue primarily to Cambodia—by strengthening investor confidence, protecting workers’ rights, and reducing operating costs for businesses.

Importantly, these goals are not new to Cambodia. The Cambodian government has repeatedly committed to governance improvement through efforts such as strengthening labor law implementation, expanding digital public services, improving the transparency of licensing processes, and increasing oversight against misconduct and corruption within state institutions. From this perspective, the agreement does not force Cambodia to “change direction”; it can be understood as a mechanism that accelerates reforms already identified as national priorities.

This comparison shows that governance clauses should not be seen only as one-sided pressure. They sit at the intersection of international conditionality and domestic political will. If managed strategically, Cambodia can transform “U.S. conditions” into tools for self-improvement, strengthening institutions and building long-term national resilience.

Conclusion

The Cambodia–United States reciprocal trade agreement is not simply a story of winners and losers. It is a difficult, high-stakes exchange at the intersection of economic rescue, export market preservation, and internal governance reform. In an era when tariffs and trade are increasingly used as political tools, Cambodia chose a path that is not surrender—but strategic calculation for survival.

In a world where major powers shape market rules and smaller states must adapt to maintain their footing, Cambodia’s case suggests that a small country does not have to become a passive victim of structural power. Instead, Cambodia can combine its domestic market, governance reform, and trade diplomacy to convert external pressure into internal opportunity.

Ultimately, this agreement reinforces a wider lesson: the survival and progress of smaller states in the global economy do not depend only on military power or market size, but on the ability to link self-reform with realpolitik—carefully, intelligently, and with long-term strategic direction.