(Phnom Penh): When the gunfire finally fell silent after 21 days of fighting—following diplomatic mediation by China and engagement by the international community—the border villages of Cambodia did not enter the kind of calm that a ceasefire is supposed to deliver. Instead, a new wave of images and videos began to surface online, posted by some Thai soldiers, purporting to show “what happened” after they entered Cambodian territory.

Yet what the world appears to be witnessing in these clips is not evidence of military professionalism or discipline. Rather, the visuals have deepened Cambodian civilians’ pain and raised serious questions about discipline, ethics, and the identity of Thailand’s armed forces in modern warfare.

This commentary reflects on the conduct shown in widely shared social-media images and videos posted after Thailand’s second outbreak of armed conflict against Cambodia—videos that emerged following Thai incursions and the occupation of certain areas inside Cambodian territory.

According to Cambodia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, during the 21-day conflict Thai forces entered and occupied locations in Banteay Meanchey, Pursat, Preah Vihear, and Oddar Meanchey. These actions, Cambodia argues, violated the ceasefire witnessed by international actors and ran contrary to Article 2(3) and Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter, which require disputes to be settled peacefully and prohibit the use of force against the territorial integrity of another state.

In addition, the conduct described intersects with core principles of international humanitarian law, including Article 53 of the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949)—which prohibits the destruction of property unless rendered absolutely necessary by military operations—and Article 52 of Additional Protocol I (1977) concerning the protection of civilian objects.

Within this legal and normative framework, acts of looting, coercion, destruction, and the filming and public posting of apparent violations involving civilian property cannot be treated as professional military conduct. Instead, they signal a profound breakdown of discipline and a troubling disregard for humanitarian norms.

Social-Media Videos: A Public Record of Conduct

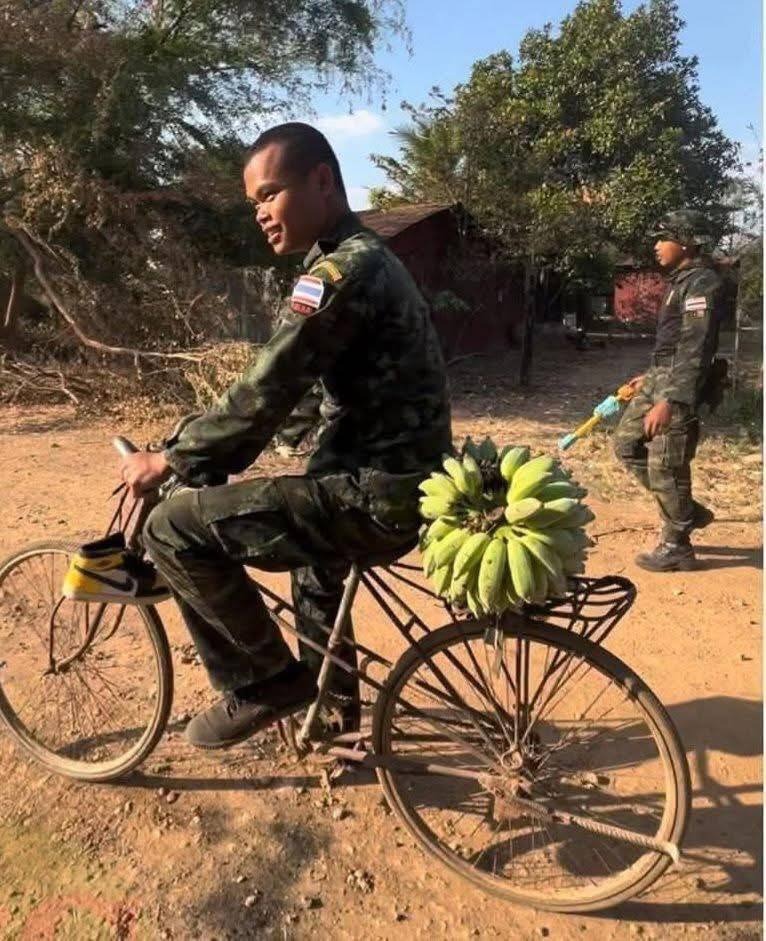

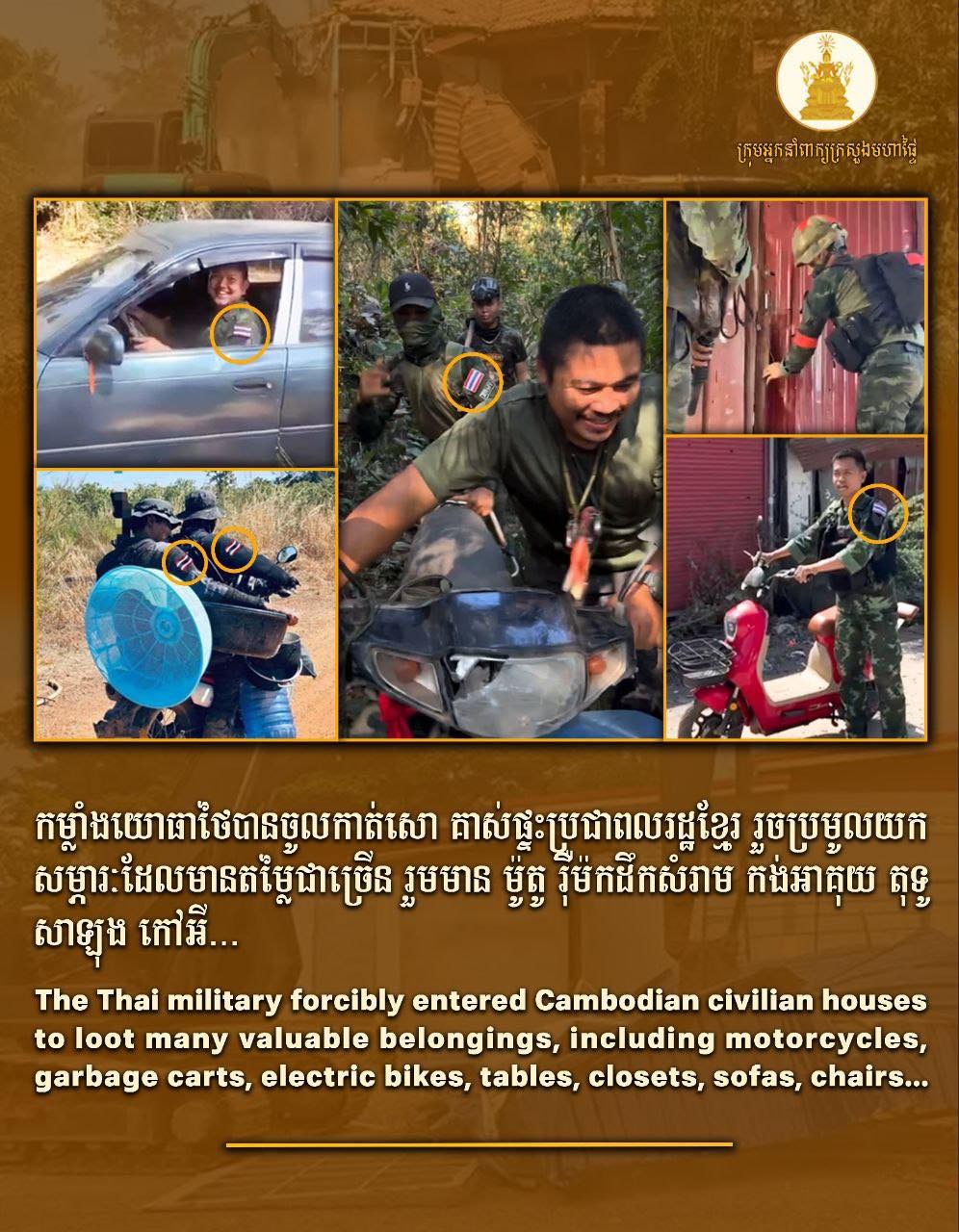

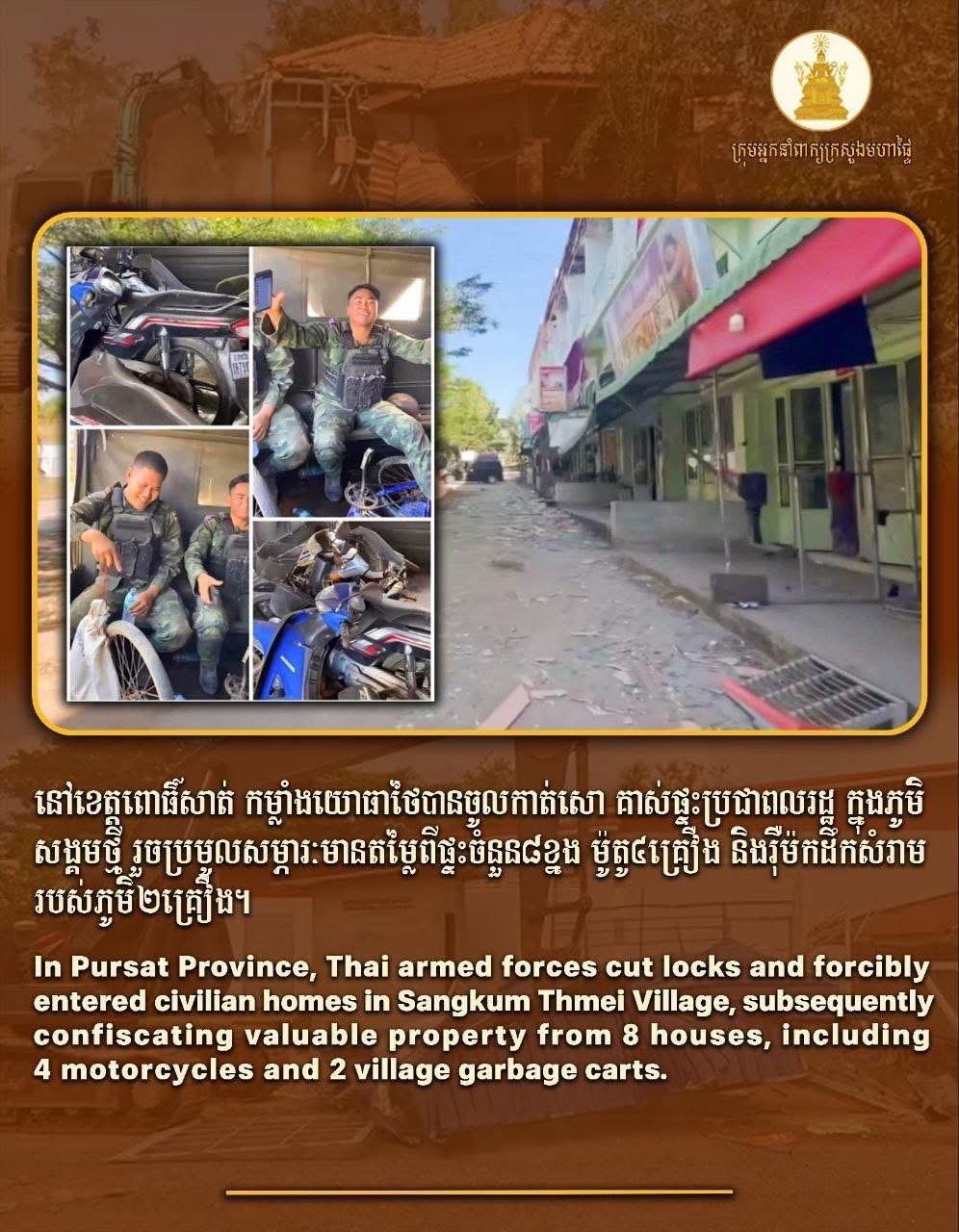

The images and videos circulating online appear to show Thai soldiers in uniform entering civilian spaces—homes and village areas—and behaving as if they are pleased to collect and take civilian belongings. Such conduct is widely perceived by Cambodian viewers as resembling criminal looting, not the behavior of disciplined soldiers.

Across international military codes, professional armed forces are taught a simple baseline: civilian property is not a prize of war. Under international law, military ethics, and many national military justice systems, theft, looting, or the seizure of public or civilian property is prohibited and often punished severely—whether it occurs during active hostilities or after a ceasefire.

Interfering with civilian property without a clear, documented military necessity—or without the consent of the property owner—violates both ethics and professional military standards. More importantly, when similar conduct appears across multiple clips from different locations, it becomes harder to dismiss as isolated misbehavior. It points instead toward systemic weaknesses in discipline, command oversight, and accountability.

What the Videos Appear to Show

Based on the publicly shared footage and images, several scenes have drawn particular outrage:

• In one clip, a soldier appears to kick a “guardian spirit shrine” (preah phum)—a sacred object in local belief—without any visible reason, raising questions about deliberate disrespect toward local culture and faith.

• Other videos appear to show soldiers burning or tearing Cambodian currency, a civilian object that poses no threat.

• In additional footage, soldiers seem to use sharp tools or weapons to damage furniture and household belongings, objects that are plainly non-military.

• Some clips give the impression of soldiers celebrating the discovery or taking of cash (including U.S. dollars).

• Other footage circulating online claims the taking of motorbikes, vehicles, household goods, kitchenware, and even domestic animals.

• Particularly painful for Cambodians, some images appear to show insulting or degrading behavior toward a royal portrait (the late King-Father), an act widely seen as a direct humiliation of national dignity.

Taken together, these images and videos—regardless of who filmed them—have become a public record that many Cambodians interpret as proof of unethical conduct by soldiers who appear to have abandoned discipline and professionalism.

Looting—And Then Posting It to Humiliate

What causes deeper pain is not only the apparent taking and destruction of property, but the decision to film it and publish it. The act of posting such content suggests the behavior is not regarded as shameful by those involved—perhaps even treated as entertainment or a trophy.

In professional armed forces, the duty of soldiers is to protect civilians, not to terrorize or humiliate them. Celebrating civilian suffering—especially in occupied villages—does not reflect military honor. It reflects a collapse of ethical standards that uniforms cannot conceal.

When the World Sees It: Can a State Escape Shame?

In today’s wars, misconduct is no longer hidden behind official statements. Conflicts are recorded in real time by cameras and shared instantly online. When soldiers in uniform are seen committing acts that resemble looting, humiliation, and destruction of civilian property, the damage extends far beyond the village. It strikes at the reputation of the state, the credibility of its institutions, and the trust of the international community.

International humanitarian law—particularly the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949) and Additional Protocol I (1977)—strictly prohibits the destruction or seizure of civilian property without imperative military necessity. In a modern conflict shaped by ceasefire monitoring and international witnesses, such acts cannot be dismissed as “minor incidents” or “accidents.” They raise questions of responsibility, including responsibility along the chain of command.

The questions the world asks are therefore not driven by nationalism, but by basic standards of civilization:

• Can any “professional” military claim discipline while conduct that appears to be looting and humiliation is displayed so openly?

• How can Thai political and military leaders explain to the international community videos that appear to show soldiers violating civilian property inside the territory of another state?

• And if such acts are captured and circulated publicly, how can a nation avoid the stigma that history attaches to documented misconduct?

In the digital era, videos do not vanish with time. They become archives—evidence that future generations can revisit when judging what happened when discipline and civilized restraint were abandoned.

Conclusion

A war may end with a ceasefire, but trust and dignity cannot be restored if military discipline is abandoned. The images and videos emerging from Cambodian villages after the 21-day conflict send a clear message: a military uniform is not a license to loot, destroy, or humiliate civilians.

If soldiers cannot respect humanitarian law and professional standards, the problem is not merely on the battlefield. It is rooted in the ethics, discipline, and command accountability that the force has lost. And when such acts are filmed and shared publicly, the world will not judge them by propaganda—but by what it can see.