(Phnom Penh): When aerial bombs fall upon ancient stone, another voice—one that cannot be destroyed by force—rises from the depths of history. It is not the sound of weapons, but the voice of ancestors: a voice carved into stone inscriptions to warn all generations that the destruction of sacred sites and cultural civilization inherited from the past never leads to true victory.

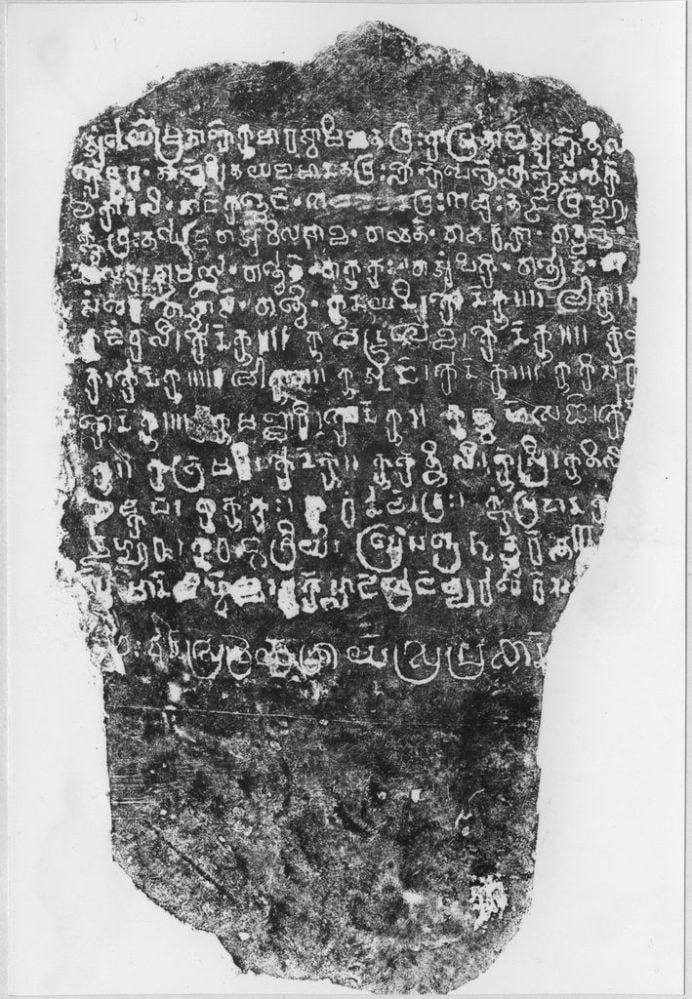

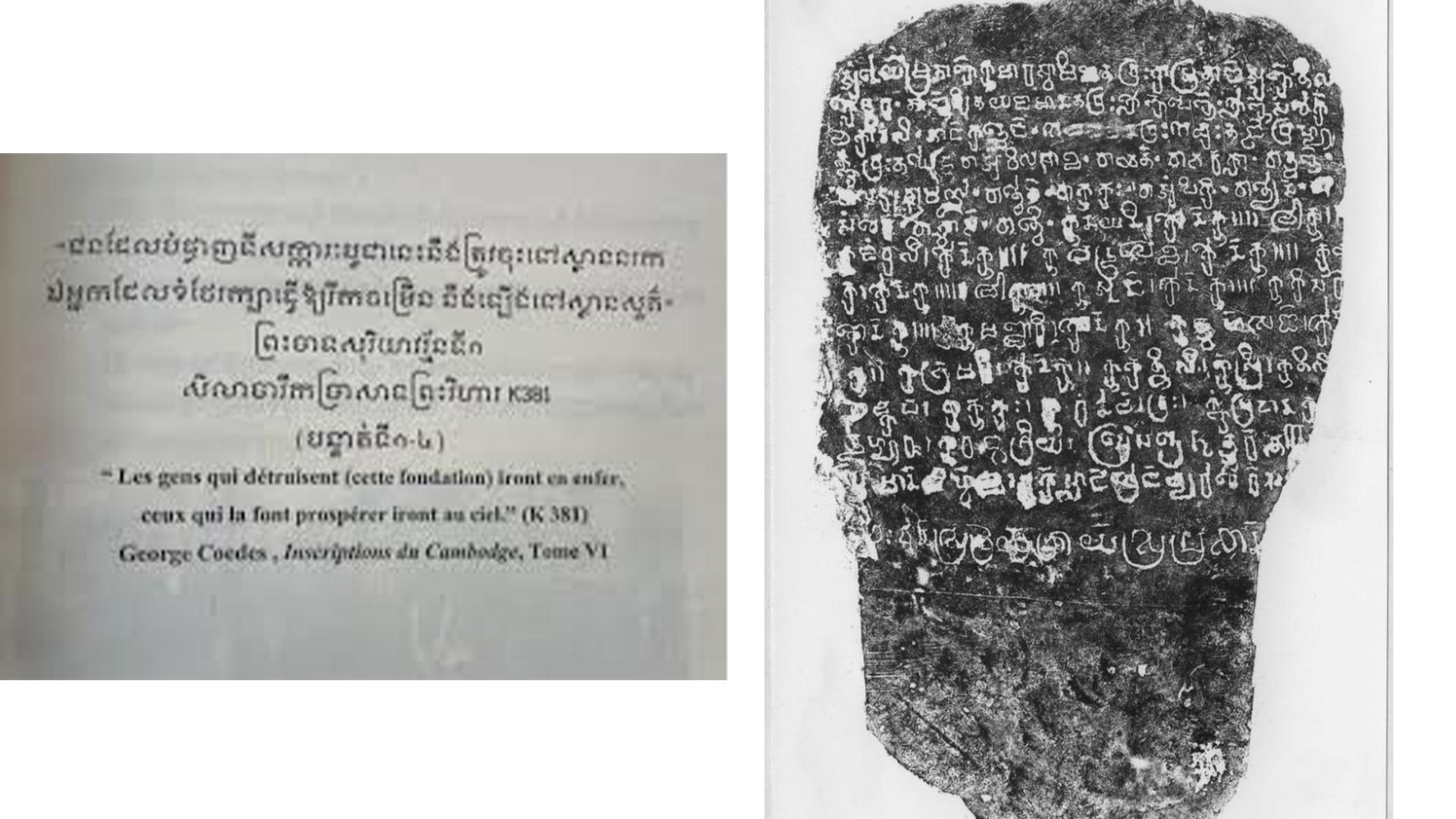

On inscription K381 (lines 1–4) at Preah Vihear Temple, the ancient Khmer king Suryavarman I left a solemn warning that echoes across centuries:

“Those who destroy this sacred sanctuary shall descend into hell; those who preserve and nurture it shall ascend to heaven.”

This curse is neither fictional nor a tool of religious intimidation. It is a moral prophecy left by the ancestors who built these temples as enduring symbols of early civilization. Its message is clear: acts of destruction against culture and civilization are not merely attacks on stone and architecture; they are acts of grave wrongdoing that inevitably generate consequences of their own. History has repeatedly shown that those who commit such acts cannot escape what may be called a “modern hell.”

Where Have Ancient Curses Manifested in History?

In eras before the United Nations or international heritage conventions existed, ancestral societies relied on religious belief and moral language to protect cultural and civilizational treasures. Curses were not weapons of immediate physical destruction like nuclear bombs; they were moral instruments—deeply embedded in belief systems—intended to restrain and punish those who committed grave transgressions.

For ancient civilizations, the destruction of sacred sites, cultural heritage, and historical monuments was never viewed as an ordinary act of war. It was considered an assault on collective identity itself—an act equivalent to erasing the soul of an entire people. Such warnings were carefully recorded by history as enduring lessons for future generations.

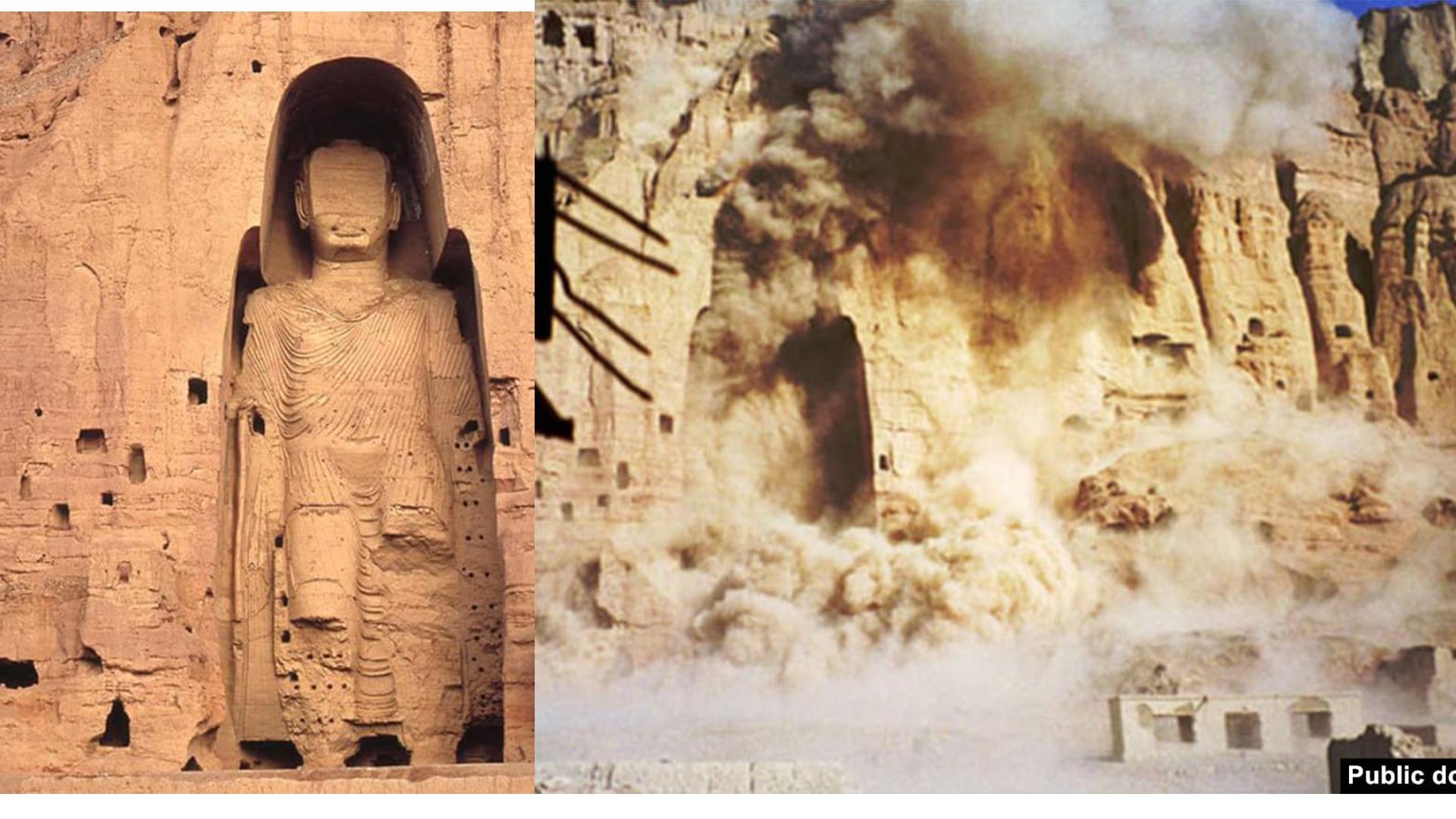

One striking example is the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001 by the Taliban. This act provoked global condemnation, stripped the Afghan regime of international legitimacy, and permanently marked it in history as a destroyer of humanity’s shared heritage. This, unmistakably, was a form of “modern hell”—a punishment from which perpetrators could not escape.

Similarly, the destruction of the Temple of Bel in 2015 by ISIS did not merely obliterate an ancient monument of world civilization. It destroyed the group’s political legitimacy, identity, and future. The international community classified the act as a war crime and an assault on civilization itself, ensuring that the perpetrators would be remembered not as conquerors, but as enemies of humanity. Once again, history delivered its verdict in the form of a modern curse.

The Curse of the Pharaohs: A Moral Warning in Modern Form

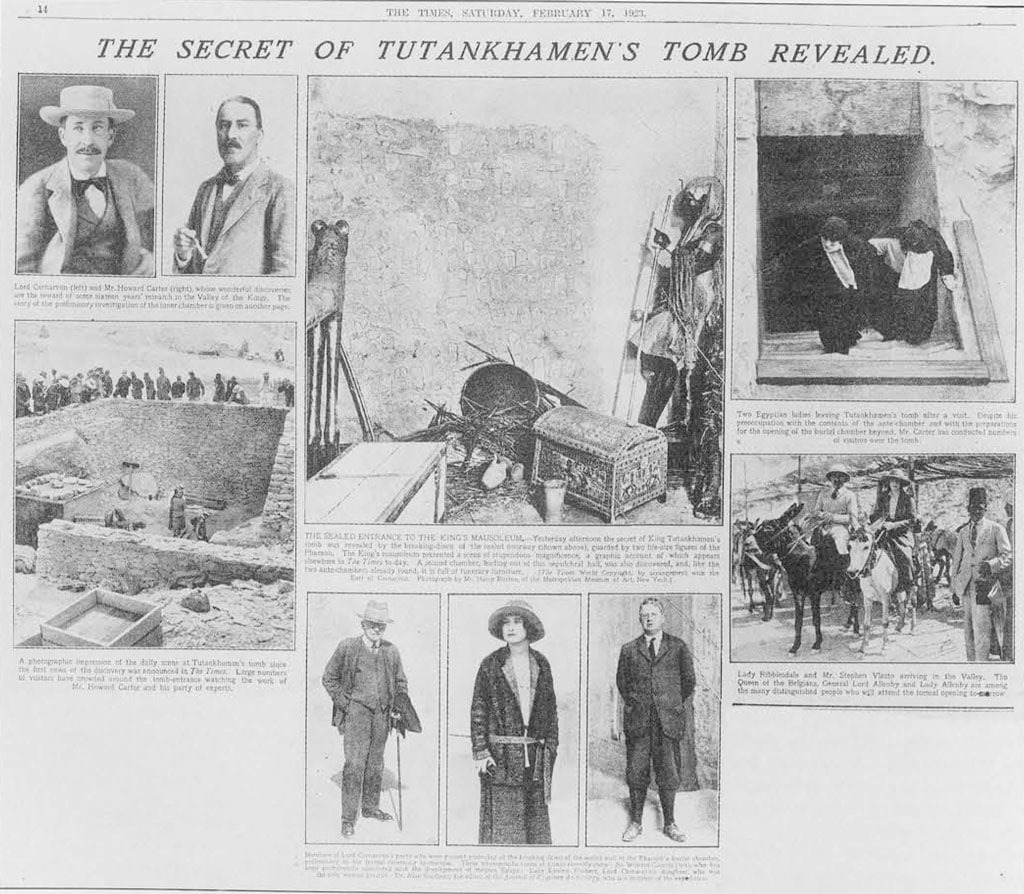

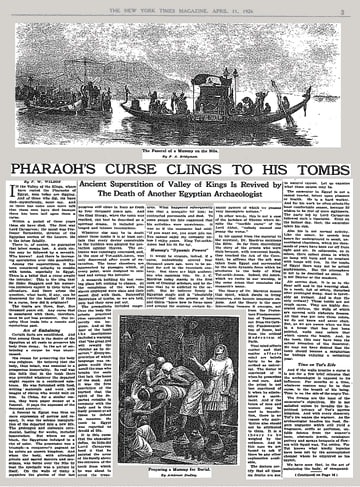

In Egypt, the discovery and opening of Tutankhamun’s Tomb in 1922 gave rise to the famous belief known as the Curse of the Pharaohs. Following the excavation, several individuals connected to the project suffered sudden illness and death, leading contemporary society to interpret these events as the result of an ancient curse.

Whether one believes in the curse or not, the episode conveyed a powerful message: the violation of sacred burial sites and the desecration of ancient heritage rarely occur without consequences. Disease, death, and intense public scrutiny became tangible forms of punishment—what many regard as another manifestation of a “modern hell.” In this sense, the curse was not mystical fantasy, but a warning translated into real-world consequences.

Ancient Curses and Modern Warfare on Khmer Soil

The recent attacks on ancient Khmer temples—including Preah Vihear, Ta Krabey, Ta Muen Thom, and Khna—have not only shattered stone and monuments. They have taken innocent civilian lives and inflicted deep wounds on the shared moral conscience of humanity. Such assaults on cultural heritage are not conventional military actions; they are attacks on universal values.

Here again, the ancient warning carved into Preah Vihear’s stone inscription resurfaces as a moral indictment of aggression and cultural destruction. These acts do not bring triumph. They lead instead to inevitable consequences—loss of legitimacy, international condemnation, and historical judgment. This is the essence of the “modern hell” that awaits those who destroy what belongs not only to one nation, but to all humanity.

Perpetrators and their accomplices cannot escape either the curse of Khmer ancestors or the judgment of the global community. If justice does not arrive today, it will arrive tomorrow. History has never absolved those who wage war against civilization.

Conclusion

Ancient curses against those who destroy cultural heritage and innocent human life are not unique to Cambodia. Across civilizations and centuries, ancestors have issued the same universal warning: grave wrongdoing inevitably produces consequences.

The words of King Suryavarman I, carved into the stone of Preah Vihear, may be interpreted by believers as a literal curse. In the modern world, they stand as a moral law—one that manifests through legal accountability, social condemnation, natural consequence, and historical judgment. Whether perpetrators are powerful leaders or seemingly untouchable figures of their time, none can permanently evade responsibility.

Those who protect culture and civilization earn honor in history. Those who destroy them live in a self-created hell of consequences. This is why the words of the ancestors must never be dismissed. They express a universal truth that remains alive today: acts of cultural destruction will always return to judge those who commit them.